2. Taxes and Fees

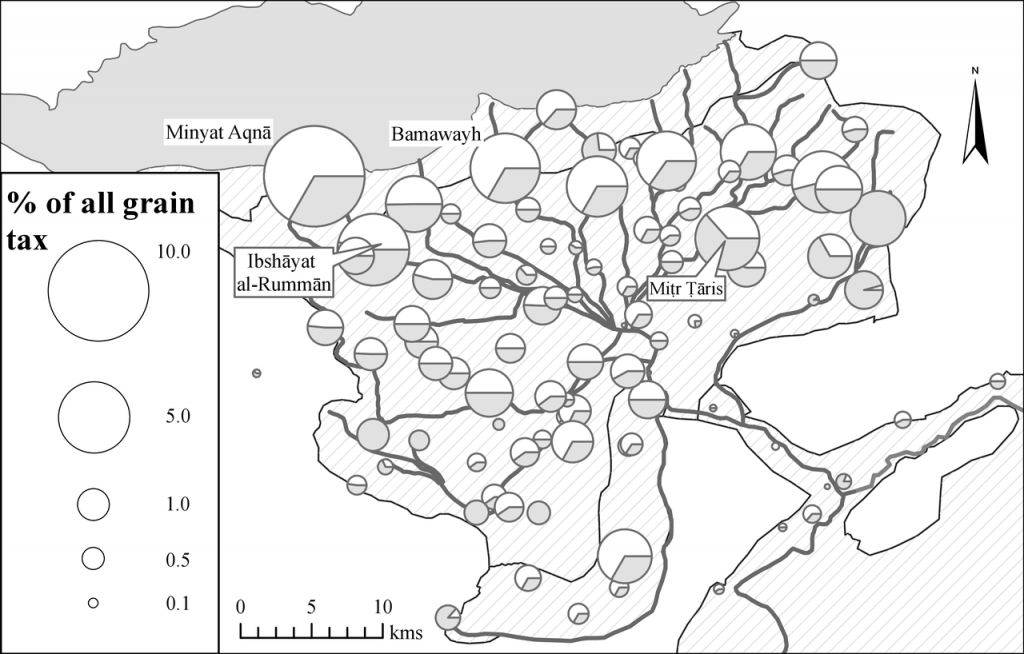

Land-Tax in Grains

Taxes in kind were mostly levied through munājaza lease contracts. In munājaza contracts, a lump sum of ardabbs of grain was assessed based on the estimated area and quality of the village’s arable lands, and was levied collectively from tenants (muzāriʿūn) of the village.

The taxes in grains consisted mainly of wheat, barley and broad beans. Beyond these staple grains, there was also a range of other summer and winter crops subject to munājaza lease contracts, including rice, Jew’s mallow, vetch, sesame, rape, cumin, and coriander. There are also rare instances where the munājaza is specified in cash, mentioned as a tax on the cultivation of cotton and lentils.[1]

The munājaza lease contract was a cheaper alternative to the expensive annual survey of individual plots.[2] The fifteenth-century author al-Qalqashandī explains that a munājaza contract is based on average yields: ‘the arable land of the village is being tendered (tunajjaz) for a specified sum not subject to decrease or increase, and the land-tax is being demanded according to that lease’.[3]

Alongside the munājaza, a minority of villages paid another category of land-tax in grains, called the mushāṭara. While mushāṭara has the apparent legal meaning of share-cropping, specifically for 50 per cent of the harvest,[4] in al-Nābulusī’s survey the term is practically interchangeable with munājaza contracts, and, because it is often specified in round numbers, does not seem to be a fixed share of the produce.[5]

Distribution of land-tax on grains; shaded areas represent non-wheat grains (barley, beans, rice)

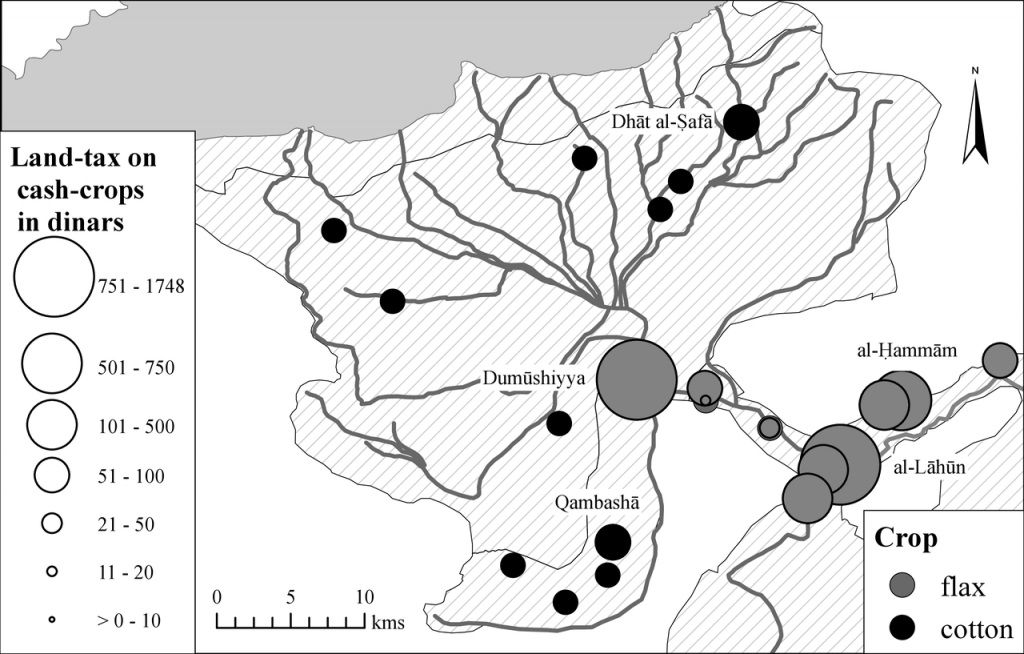

Land Tax on Field Cash-crops

Fields of winter and summer cash crops, including the widespread flax, were subject to a ‘land-tax on feddans’ or ‘cash land-tax on feddans’ (kharāj al-fudun, mufādanāt, kharāj fudun al-ʿayn). These were taxes on field cultivation, paid in cash according to a scale of tax-rates per feddan. Crops subject to this land-tax in cash were flax, cotton, garlic, colocasia, alfalfa, green vegetables, cucurbitaceous fruits, and carrots.

The amount of tax to be paid was calculated according to the area of cultivation (given in feddans) multiplied by the tax-rate (qaṭī‘a), which depended on the crop. Al-Nābulusī sometimes provides both the area under cultivation in feddans and the tax assessment in dinars, or sometimes — especially for flax and cotton — just the tax assessment.

The tax-rates mentioned are 1 dinar per feddan on alfalfa;[6] 2 dinars per feddan on garlic,[7] green vegetables (khuḍar),[8] henna, indigo,[9] and cucurbitaceous fruits;[10] 3 or 5 dinars per feddan on colocasia;[11] and 3 or 5 dinars per feddan on flax. Cotton was mostly taxed at a rate of 1.5 dinar per feddan, but rates of 1.25 dinar or 2 dinars per feddan are also mentioned.[12]

The cash crop tax category was supplemented by an ‘addition’ (iḍāfa), a 12.5 per cent surcharge over the basic tax.

Data: Land Tax on Field Cash Crops

Map: Land-tax on flax and on cotton

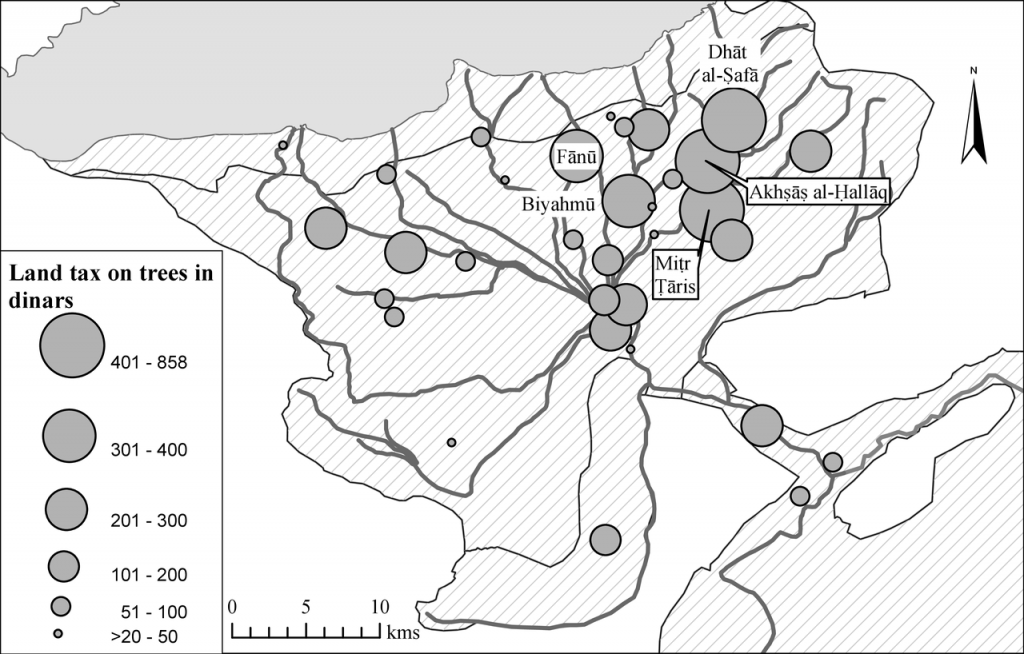

Land-Tax on Orchards, Palm Enclosures, and Vineyards

The taxes on orchards and vineyards were levied through a category of ‘land-tax on perennial trees and water-wheels (kharāj al-rātib wa’l-sawāqī)’. As the name suggests, this tax was closely associated with year-round irrigation by water-wheels. The tax was levied per feddan and was probably collected in Madīnat al-Fayyūm upon the sale of the produce, a method attested in fourteenth-century Damascus.[13]

Orchards were subject to a standard tax-rate of a 2 dinars, supplemented by a 12.5 per cent surcharge. Land designated for viniculture was subject to a higher rate of 5.33 dinars, plus a surcharge of 12.5 per cent. Young trees were subject to lower rates. Unlike field cultivation, orchards and enclosures were akin to private property, and there are references to named individual owners.

Also included in this category were taxes on lands designated as long-term leases (aḥkār). The terms of these long-term leases allowed the lessees freedom of use, but it seems they were mostly planted with trees and vines. Lands subject to long-term leases paid the same rate as orchards, 2 dinars per feddan, made up of a basic tax-rate of one dinar per feddan and an additional tax-rate of another dinar per feddan.

Data: Land tax on Orchards Palms Enclosures and Vineyards

Map: Land-tax on orchards and vineyards

Lunar-calendar Taxes on Trade (al-māl al-hilālī)

Taxes on trade were due from sites of commercial activities, mainly shops, usually in the form of rent or concession. These were known as ‘lunar calendar taxes’ (al-māl al-hilālī), since they were paid monthly and followed the Islamic, lunar, calendar. This category occasionally also included agricultural activities that did not depend on the solar calendar, such as fishing and pasture.

The taxes on trade were levied as rent paid for the usufruct of buildings and structures, such as water-mills, store-houses (ādur), weavers’ pits, pottery kilns, tanneries, shops, and bath-houses.[14] Often, the taxes on trade are described as ‘rent of the Dīwān’s shops’, ‘rent of the shops’, or simply revenues ‘from the shops’, a catch-all category that included small-scale artisanal workshops.

The term surety or concession (ḍamān) is also used to designate rent payments on shops, as well as concessions for the operation of ferryboats and the sale of chicken.

Data: Commercial taxes (lunar calendar taxes)

Fees (rusūm)

The process of harvesting, measuring, threshing, and transporting grains was subject to an array of fees, reported in a separate section of the tax record for each village. The fees also included payments to local officials and set payments for armed protection and for religious services. None of these fees is adequately explained in the administrative literature.[15]

1. A threshing-floor fee (rasm al-ajrān), in cash and in grains, is mentioned in nearly all villages which were subject to land-tax in grains. The threshing floor payments in grains are sub-divided into the different types of crops. For every ardabb of grains paid in threshing-floor fees, cultivators had also to add 0.8–0.9 dirhams in cash.

2. A separate measurement fee (al-kiyāla) was paid in kind, again sub-divided into different categories of grains. The total amount of the measurement fees in kind is roughly equivalent to the total threshing-floor fees, but there is no consistent correlation between the two categories of fees.

3. A surcharge payment, called wafr, is attested in nine villages with very high grain production. It was calculated as an additional 3 per cent on top of the land-tax in kind.[16] A handful of very large villages also had to pay a transport fee, with an inconsistent rate.

4. A uniform harvest fee (rasm al-ḥiṣād) of 53 dirhams was levied in nearly all grain-cultivating villages in the province, regardless of the amount of grains they were expected to produce.[17]

5. A uniform and modest protection fee (rasm al-khafāra) was collected from most villages, at a fixed value of 15 dirhams. This minimal and uniform tax appears to be a blanket policing fee.[18]

6. A fee for ‘supervision of cash payments’ (shadd al-ʿayn), found in about half the villages in the Fayyum, was linked to the collection of cash land-tax on field crops. The largest fees are found in villages which also had substantial cash-crops, especially flax.

7. A ‘dredging fee’ (rasm al-jarārīf) was paid by most villages that lay along gravity-fed canals (a total of sixty-two villages), averaging at around 1 dinar per village. It is not found in villages that relied on basin irrigation.

8. About half the villages along gravity-fed canals made small payments of grains to the official known as khawlī al-baḥr (The Canal Controller), who was in charge of the schedule of opening and closing of weirs.

9. A minority of villages paid their taxes on cash field crops in the form of fees, sometimes called ‘settlement’ (muṣālaḥa). This was common with less valuable field crops, such as carrots, where the tax-collectors dispensed with the costly land survey and collected the taxes as fees based on estimates.

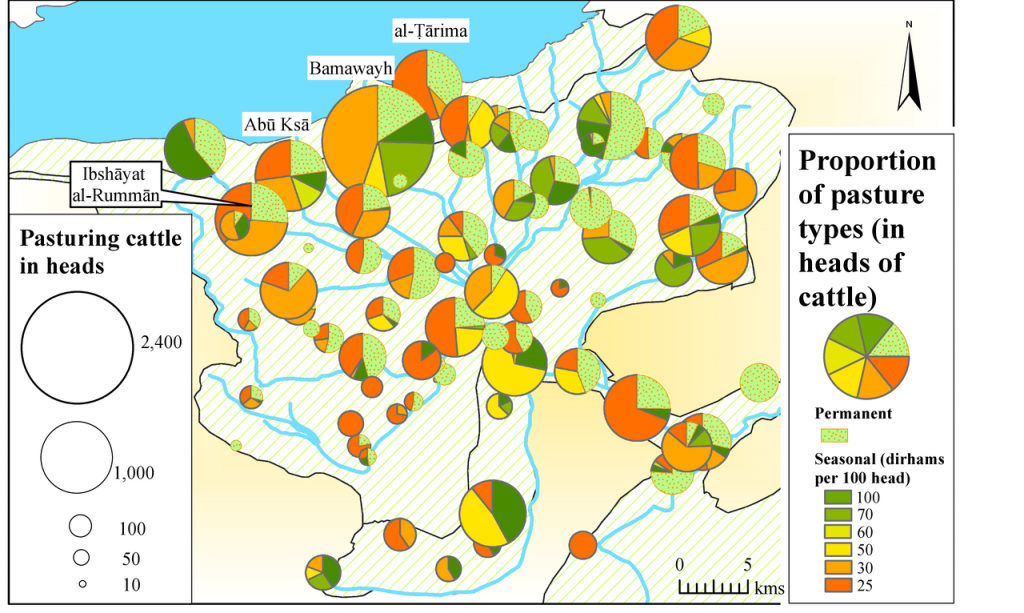

Pasture Fees

A complex set of fees governed a strict monitoring of grazing. Pasture areas were divided into permanent areas of high quality, known as rātib,[19] and seasonal or occasional pasture lands called ṭāriʾ, sub-divided according to their quality. Each category of pasture area was assigned a tax-rate per head of grazing animal.[20]

The fee for the permanent pasture areas was set at 2.25 dirhams per head of livestock. The fees for seasonal grazing areas were subject to a scale of rates, from 1 dirham per head to 0.25 dirhams per head, apparently depending on the quality of the pasture.

The tax collection and counting of animals was administered by a group of clerks, who received a ‘government agents’ fee’ (rasm al-mustakhdamīn), calculated as 6.25 dirham per hundred heads of livestock.[21] The assumption appears to be that the animals remained in the same pasture area throughout the entire season.

Permanent pasture lands (rātib) were sometimes subject to a fixed pasture-tax (māl al-marāʿī), regardless of the number of grazing animals. It was also called the ‘permanent pasture-tax’ (marāʿī rātib). A fixed tax on permanent pasture lands was a simpler alternative to the collection of fees per head, and obviated the need to count the numbers of livestock entering the pasture area.[22]

Map: Permanent and seasonal pasture areas, by number of grazing animals

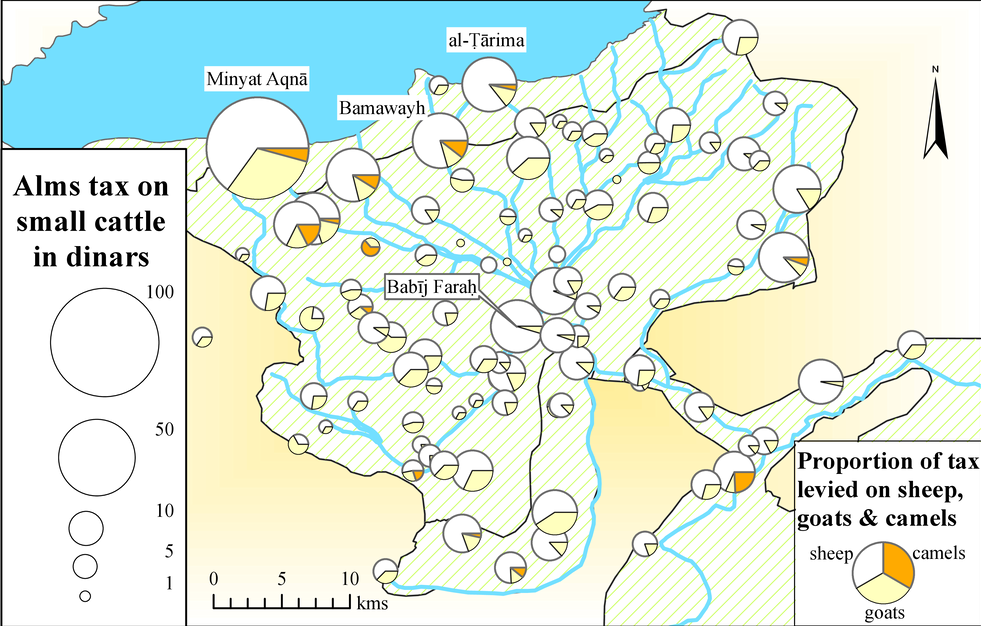

Alms-tax (zakāt)

Islamic alms-tax, the zakāt, was reintroduced to Egypt by Saladin as part of an Islamization project.[23] In Ayyubid Fayyum, it was levied on livestock, categories of dry fruits, capital, and slaves.

1. The principal concern of the alms-tax was livestock. Payment was required from freely pasturing herds or flocks of large and small cattle in full private ownership.[24]

For cows and buffalos, one year-old calf (tabīʿ) was levied from a herd of more than thirty cows, and one cow in her second year (musinna) for every forty heads.

The alms-tax on sheep and goats was one sheep or goat for a flock of over forty heads, two for 120–200 heads, and then a rate of one animal for every additional hundred. Camels were paid for in heads of goats, one goat for every five camels.[25] The terms used for small livestock are bayāḍ (lit., ‘white’) for sheep and shaʿriyya (sing.; pl. shiʿārā) for goats. These terms also appear in Ibn Mammātī’s section on the alms-tax.[26] Occasionally, a distinction is made between the local small cattle (qarāriyya) and transient small cattle (muntajiʿūn).

The alms-tax was specified in heads of animals, but actual payment was taken in cash, after the monetary value of the animal was assessed. For example, each head of sheep levied in alms-tax was commuted to around one gold dinar.[27]

2. Alms-tax, probably at a rate of 5 per cent, was levied on the dry fruit of date-palms, vineyards, and olives. This alms-tax was levied on privately owned trees and, according to legal literature, was supposed to apply above a minimum threshold of five awsāq (about 610 kg). In the Villages of the Fayyum, The alms-tax was limited to these three varieties of dry fruit, in line with Shāfiʿī and Mālikī doctrine.[28] Ibn Mammātī reports that alms-tax is levied on the fruits of the date-palm and the grape-vine, but exempts olives.[29]

The alms-tax on these fruits was calculated as an estimate (kharṣ) of the yield. In Islamic law, the alms-tax on grapes, dates, and olives was calculated when the fruits were yet unpicked, leading to an estimate of the projected yield as dried fruit.[30]

3. Alms-tax was also levied on commercial capital and on slaves. According to legal texts, the alms-tax on capital and on slaves was at a rate of 2.5 per cent, above a minimum threshold of 20 dinars. This category was levied almost exclusively in Madīnat al-Fayyūm, suggesting that neither capital nor slaves were widely available beyond the city.

Map: Alms-tax on small cattle

Payments for Minisrty of Religious Endowments (Dīwān al-Aḥbās)

The majority of villages, sixty-one settlements, were subject to a tax on religious services paid to the Ministry of Endowments of Congregational and Neighbourhood Mosques. The tax ranged from 0.5 dinar in small villages to a significant 20 dinars in al-Lāhūn.

A small fee, in dirhams, was paid in the same villages for the upkeep of local religious buildings. This fee was closely correlated with the tax due to the Ministry, as a rate of 2–3 dirhams to every dinar of tax (5%–7.5%).

Data: Payments for Muslim Religious Endowments

Poll-Tax

The poll-tax (al-jawālī; the legal term jizya does not occur) was levied at a flat rate of 2 dinars per annum on every non-Muslim adult male, in agreement with evidence regarding contemporary practice elsewhere in Egypt. While the majority of the Sunni schools of law exempt the poor, or those incapable of paying, Fatimid and Ayyubid policies were generally to grant no exemptions and to levy a flat rate.[31]

The collection of the poll-tax was undertaken by officials called ‘beast-chasers’ (ṭarrādūn al-waḥsh; also once in singular, ṭarrād al-waḥsh). These officials were given a small annual payment of 0.5 dinar each, deducted from the government’s poll-tax revenues.[32]

In the poll-tax register, a quarter of Fayyumi non-Muslims were registered as absentees, either in Upper or in Lower Egypt.

Hay Levy

All grain-producing villages were liable to a levy of hay (muwaẓẓaf al-atbān), that is, the stalks of grains after the harvest, measured in bales (shanīf).[33] The hay levy is discussed by Ibn al-Mammātī, who describes a complex tax of which we have only an occasional trace in the treatise. According to Ibn Mammātī, the levy was divided up between the Dīwān, the iqṭāʿ-holder and the cultivator. The cultivator could buy the Dīwān’s share for cash, at a rate of 4.16 dinar per hundred loads (ḥiml).[34]

Foodstuff Levy

Iqṭāʿ-holders were entitled to small amounts of cereal dishes of three varieties: kishk (dried yogurt with crushed wheat), sawīq (parched grain with butter and fat), and farīk (green wheat). These taxes were levied in kind, specifically for the benefit of iqṭāʿ-holders, and are called in literary sources ‘hospitality dues’ (ḍiyāfa), although the term is not mentioned in al-Nābulusī’s text.

Poultry Levy

A levy of chickens is mentioned in eighty-seven villages, amounting to about 55,000 birds. The local tenant cultivators reared chicks, which probably hatched in two major hatcheries (sing. maʿmal al-farrūj) in Madīnat al-Fayyūm and Sinnūris. The villagers delivered the mature birds either to the government’s kitchens or to the local iqṭāʿ-holders. In return they received a ‘rearing wage’ (ujrat al-tarbiya) of one-third of the amount of chickens they were due to deliver.

There are no taxes on chicken, and it seems that poultry production was not permitted beyond this network of hatcheries and village rearing. Monopolies over the sale of chicken are mentioned in two villages, where small payments for the concession of chicken (ḍamān al-farrūj) are mentioned. This may represent a system where a contractor (ḍāmin) held a monopoly over the sale of chickens in a given area, as reported for the early Mamluk period.[35]

Data: Poultry levy (chicken breeding)

[1] Munājaza tax on Cotton: Tuṭūn and Buljusūq; on lentils: Miṭr Ṭāris. Unspecified munājaza in cash: Ghābat Bāja and Dumūshiyya.

[2] Abū al-Ḥasan Ibn ʿUthmān al-Makhzūmī, Al-muntaqā min kitāb al-minhāj fī ʻilm kharāj Miṣr, ed. by Claude Cahen and Yūsuf Rāghib (al-Qāhirah: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1986), p. 59 (fol. 166r). See also Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 189.

[3] Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ, iii, 458.

[4] For a mushāṭara contract from the early Mamluk period in which the produce is divided equally between the landlord and the peasant, see Taqī al-Dīn Ibn Taymiyya, Majmūʿat al-fatāwā li-Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymīya, ed. by ʻAbd al-Rahṃān ibn Muḥammad Ibn Qāsim and Muḥammad ibn ʻAbd al-Rahṃān Ibn Qāsim (Riyadh: Matābiʿ al-Riyād,̣ 1961), xxx, 119–20.

[5] Ibn Mammātī makes it clear that land subject to mushāṭara pays its taxes in kind, but he does not elaborate; Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. ʿAṭiya, p. 259; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 115 (6.3.14). Al-Makhzūmī distinguishes between land-tax on ‘feddans of cash and of grains’ and feddans of mushāṭara; Makhzūmī, al-minhāj, p. 60 (fols 166v–167r). Cahen equates munājaza and mushāṭara and defines them as the dividing of the total tax of a villages among the individual taxpayers. See his ‘Contribution á l’étude des impots dans l’Égypt médiévale’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 5 (1962), 244–78 (p. 264); Cahen, ‘Le régime des impôts’, p. 14. See also Rabie, The Financial System, p. 75; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 190 (‘the process whereby an assessment for an entire district was handed down by the central government and then apportioned among the taxpayers of the district’). See also Cooper, ‘The Assessment and Collection of Kharāj Tax in Medieval Egypt’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 96. 3 (1976), 365–82.

[6] Compare Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 117 (6.3.6), although Ibn Mammātī says there is disagreement on this tax-rate.

[7] Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 117 (6.3.7).

[8] Ibn Mammātī reports tax-rate of 2 dinars for lettuce and cabbage; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 121 (6.4.12, 6.4.13).

[9] Ibn Mammātī has 3 dinars for indigo; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 120 (6.3.6, 6.4.09).

[10] Ibn Mammātī has 1–2 dinars; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 118 (6.3.6, 6.4.02).

[11] Ibn Mammātī has the current tax-rate as 4 dinars per feddan, down from 5 under the Fatimids; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 120 (6.4.06).

[12] Ibn Mammātī has cotton taxed at 1 dinar per feddan; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 119 (6.4.04).

[13] Taxes on the fruits and vegetables grown in Damascus were levied after the produce was brought to a central location, called Dār al-Biṭṭīkh wa’l-Fākiha (‘Hall of Melons and Fruits’), to be sold and taxed there. See Mathieu Eychenne, ‘La production agricole de Damas et de la Ghūta au xive siècle: diversité, taxation et prix des cultures maraîchères d’après al-Jazarī (m.739/1338)’, Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient, 56. 4–5 (2013), 569–630 (p. 597).

[14] On this category, see al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-arab, viii, 228. Al-Nuwayrī explains that rent (ujra) is levied on covered, or roofed, properties, while surety (ḍamān) is levied on uncovered properties.

[15]Al-Nuwayrī states that cash fees (ḥūqūq) were paid on every feddan of grain cultivation, at a rate of 2–4 dirhams per feddan; al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-arab, viii, 249. Note that in the Villages of the Fayyum the fees are mostly specified in kind and not in cash.

[16] According to al-Nuwayrī, a payment called wafr was to be taken from the officials in charge of measuring the grains and buying the crops for cash. In his account the wafr seems akin to a fee; al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-arab, viii, 252, 296.

[17]The tiny village of Dimūh al-Dāthir was liable to only 25 dirhams, and was also exempt from the ‘protection fee’, so must have had its unique arrangements.

[18] This is perhaps the same fee as the one mentioned by al-Nuwayrī in connection with the measurement of crops; al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-arab, viii, 296.

[19] The terminology here is similar to that used for non-Muslims subject to the poll-tax, where rātib is a local established resident, ṭāriʾ is a new-comer, and nāshiʾ is one who recently became adult; al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-arab, viii, 242.

[20] Al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-arab, viii, 191, 262. See also Rabie, The Financial System, p. 79.

[21] See Rabie, The Financial System, pp. 79–80. Rabie argues that the categories of the pasture fee depended on the size and age of the animals.

[22] The two categories of taxes on permanent pasture — fees based on the number of animals and the fixed pasture tax — are mentioned together only in the entry for the village of Shisfa.

[23] Rabie, The Financial System, p. 96; Aron Zysow, ‘Zakāt’, EI2, xi, 406–22.

[24] According to a view ascribed to al-Shāfiʿī, even one day of feeding on fodder would exempt the owner of an animal from paying alms-tax; the Ḥanbalīs view this as a loophole; Ibn Qudāma, al-Mughnī, iv, 13. The dominant opinion cited by al-Nawawī is that animals are subject to alms-tax as long as the fodder they receive is not necessary for their survival, which would mean up to three days of fodder. See Yaḥyā bin Sharaf al-Nawawī, Kitāb al-majmū‘: Sharḥ al-muhadhdhab, ed. by Muḥammad Najīb al-Muṭī‘ī, 12 vols (Beirut: Dār Iḥyā’ al-Turāth al-‘Arabī, 2001), v, 231.

[25] Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. by ʿAṭiya, pp. 311–12; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, pp. 266–67.

[26] Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. by ʿAṭiya, pp. 351–52.

[27] This is again in line with Ibn Mammātī’s recommendations. Al-Makhzūmī is more specific in this regard, stating that the alms-tax on livestock could be levied by the actual sale of the animals or by monetary valuation (tathmīn). See Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, pp. 291–92.

[28] Al-Nawawī, Kitāb al-majmū‘, v, 310.

[29] The fruits are named as raisins (zabīb) and dates (tamr). Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 267.

[30] This is because the alms-tax on fruits is due when the fruits first appear to be good (badā ṣalāḥuhā). See Ibn Qudāma, al-Mughnī, iv, 169, 173; al- Nawawī, Kitāb al-majmū‘, v, 325 ff.

[31] This conclusion is based on ample evidence from the Geniza. See Eli Alschech, ‘Islamic Law, Practice and Legal Doctrine: Exempting the Poor from the Jizya under the Ayyubids (1171–1250)’, Islamic Law and Society, 10. 3 (2003), 348–75 (p. 373). Ibn Mammātī, however, still reports rates of 4 1/6 dinars for the rich, 2 dinars as medium rate, and a low rate of 1 7/12 dinar (1.58) for the poor. See Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. by ʿAṭiya, p. 31.

[32] Ibn Mammātī reports that the poll-tax collectors receive a fee of 2 1/4 dirhams per head; Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. by ʿAṭiya, p. 319.

[33] Cahen, ‘Le régime des impôts’, p. 22 n. 3.

[34] Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. by ʿAṭiya, p. 344; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, p. 288.

[35] Rabie, The Financial System, p. 103.