4. Sugarcane

Sugar-cane was mostly grown on crown estates, called ūsīya (pl. awāsī). The crown estates were separate from the main lands of the village and were owned by the Dīwān al-Māl, so were not subject to tax. Instead of taxes, al-Nābulusī records the numbers of feddans of crown estates in the village and their use.

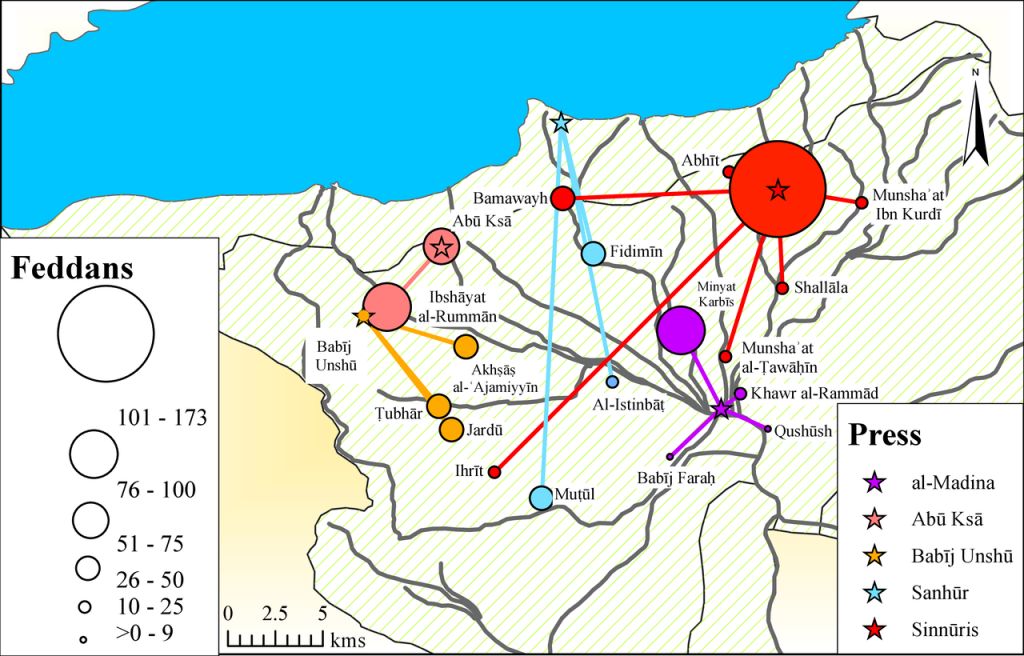

The sugarcane plantations fed thirteen sugarcane presses, each with one or more pressing-stone, turned by oxen or by water. Each pressing stone was allocated 35–90 feddans of sugarcane. When a sugarcane press was located in the village, al-Nābulusī also lists the feddans of sugarcane and fodder assigned for its supply, which may be located not only in the village itself but also in several nearby villages.

Al-Nābulusī states that the crown estates consisted of 1,654 feddans, of which the vast majority (1,468) were devoted to sugarcane, and the remainder mostly sown with fodder for livestock used for turning the sugar presses. A couple of crown estates were used for crops other than sugar — flowers, fruits, and vegetables in the city, barley and sesame in Ṭalīt in southern Fayyum.

The sugarcane plantations were divided into first and second harvests, with the area of the first harvest always several times larger than the area of the second harvest. A first crop (raʾs), was planted in March and harvested on January of the following year. After the first harvest, the field was set on fire; the ratoons that emerged after the fire were irrigated until a second harvest (khilfa) took place in November–December. Following this two-year cycle, the land had to be left fallow.[1]

Labour for the sugarcane plantations came from villagers, employed either as tenants (muzāriʿūn) or as quarter-share wage-labourers (murābiʿūn).[2] In Islamic law, a murābaʿa contract stipulated that a manual labourer only contributed his labour, while seeds and beasts of burden were provided by the land-owner. In return, the murābiʿ was to receive a quarter of the yield. In practice murābaʿa meant wage-labour. But because it was technically a share-cropping contract, the remuneration the murābiʿūn received was classified under the category of seed advances (taqāwī).[3]

A handful of villages have references to taxes on canes, which may be either sugar-cane or a variety of reeds with no juice, known as Persian cane (qaṣab fārisī).[4]

Map: Network of sugar-cane presses and plantations

[1] Tsugikata Sato, Sugar in the Social Life of Medieval Islam (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 34–48; Sato, ‘Sugar in the Economic Life of Mamluk Egypt’, Mamlūk Studies Review, 8. 2 (2004), 87–107 (p. 96).

[2] On the murābiʿūn in later periods, see Kenneth M. Cuno, The Pasha’s Peasants: Land, Society and Economy in Lower Egypt, 1740–1858 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 181.

[3] This created an artificial parallel with the seed advances handed over to tenant-cultivators of grains, even though the wage-labourers used the cash and grains for sustenance. This point has already been made by Sato, State and Rural Society, p. 219.

[4] While originally another name for sugarcane, Ibn al-Nafīs refers to qaṣab fārisī as a reed with no juice. Ibn Mammātī also mentions a rate of 3 dinars per feddan for the cultivation of Persian canes, separate from sugar-cane; Sato, Sugar, pp. 30, 98–99.