1. The Village

Throughout the Villages of the Fayyum, the village as a unit of agricultural production is called nāḥiya. The nāḥiya was the administrative building block for the allocation of land and water resources and payment of taxes. When referring to the physical space of the village, al-Nābulusī usually uses the terms balad or balda.[1]

Hamlets (kafr, pl. kufūr; also called munshaʾa, pl. manāshiʾ) were smaller settlements, whose taxes were normally subsumed under the tax-entry of a mother village. A list of the manāshiʾ, organized by their mother villages, is provided towards the end of the treatise. Hamlets were also dependent on a mother village for their water quota. Some hamlets paid alms-tax on livestock separately from their mother village, even if all other taxes, including the land-tax, were paid jointly.

Fiscal Revenue and Iqṭāʿ

Most of the villages in the Fayyum were assigned to holders of iqṭāʿ grants. The holders of the iqṭāʿ grants were officers in the Ayyubid army who had temporary rights to the fiscal revenue (irtifāʿ) in the village in return for providing military service.

The fiscal revenue allocated to iqṭāʿ-holders normally included the land-tax, both in cash and in kind, and the commercial taxes. The remaining taxes, including the alms-tax on livestock, the poll-tax on non-Muslims, and fees on the use of pasture, went to the state treasury, the Dīwān al-Māl. The Dīwān al-Māl also owned the sugarcane plantations and presses.[2]

A handful of villages were not granted to iqṭāʿ-holders. Most prominently, these were three large villages that belonged to the private domain (khāṣṣ) of the Sultan. In these three villages the Sultan had a personal right to the fiscal revenue, paralleling those of iqṭāʿ-holders in other villages.

In addition, three small villages and some individual orchards were endowed as waqf for the benefit of religious institutions, both in Cairo and in Madīnat al-Fayyum. This meant that their fiscal revenues were channelled for the support of the endowed institution.

Fiscal Value

When a village (or, sometimes, a group of villages) was granted as iqṭāʿ, it was accorded a fiscal value (ʿibra), designated in a nominal unit of account known as Army Dinar (dīnār jayshī). The Army Dinar was supposed to create a standard measure of the income an iqṭāʿ unit was expected to generate, which could then be matched with the rank of the recipient of the iqṭāʿ.

Ibn Mammātī states that the Army Dinar was calculated by adding the expected income in ardabbs of grain to the cash revenue, in gold dinars, multiplied by four. Al-Qalqashandī explains that under the Ayyubids each Army Dinar was worth three gold dinars.[3] In the Villages of the Fayyum, however, the value of the Army Dinar is not standard.

Iqṭāʿ units usually consisted of a single village, but an iqṭāʿ unit could also consist of a cluster of villages, mostly along the same irrigation canal. The largest clusters of this kind were the Dilya Canal, in south-western Fayyum, which included twelve different villages, and the Tanabṭawayh Canal, also in the south. In villages that formed part of these multi-village iqṭāʿ units, the fiscal value mentioned is of the total iqṭāʿ unit to which the village belonged.

Bedouin and Non-tribal (badw and ḥaḍar)

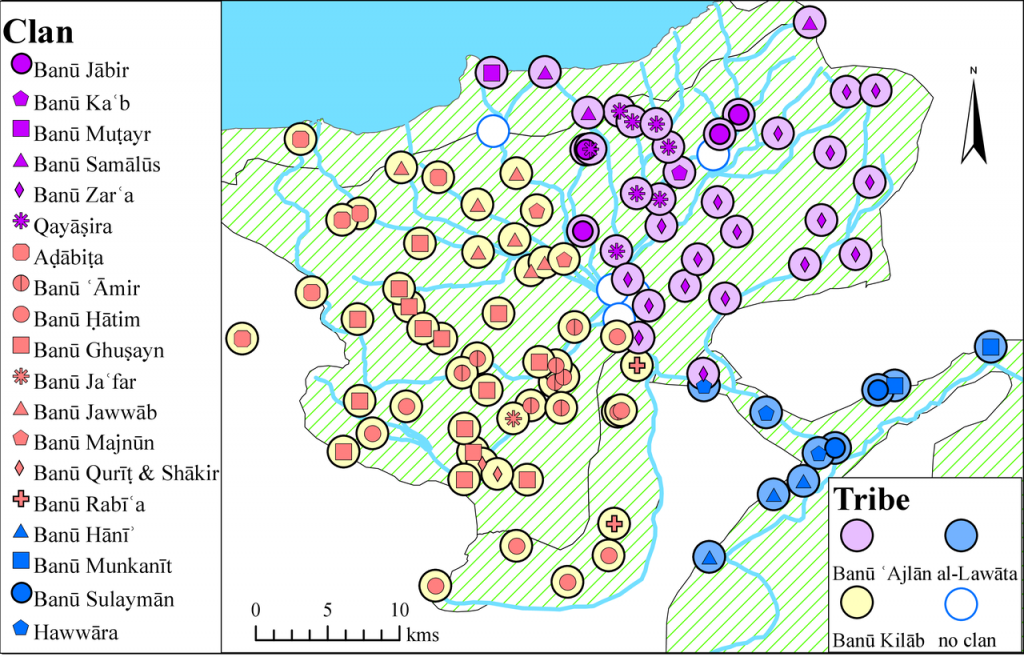

Nearly all villages and hamlets in the Fayyum were inhabited by Arab tribesmen, also called badw, or Bedouin. Each village was identified with a tribal section or clan. While the Arabs were the inhabitants in most villages, a handful of villages were inhabited by predominantly non-tribal, or clan-less (ḥaḍar) population. In these villages, the Bedouin were the guardsmen or protectors (khufarāʾ).

The segmentary tribal structure is described by al-Nābulusī in his introductory chapters. At the top level were three tribal confederacies (aṣl or āl), each inhabiting a large number of villages. First in importance were the Banū Kilāb, with as many as fifty villages, followed by the Banū ʿAjlān and the much smaller Lawāta, a Berber tribe. The Banū Kilāb dominated in the centre, south, and west; the ʿAjlān in the east and the north; while the Lawāta dwelt in villages along the al-Lāhūn gap.

Each tribal confederacy was divided into sections or clans, which al-Nābulusī usually calls fakhdh (pl., afkhādh) or ‘branch’ (farʿ). Each tribal section inhabited a varying number of settlements, from one hamlet (the Banū Muṭayr in Sanhūr) to as many as nineteen villages (the Banū Zarʿa of the ʿAjlān). The individual village entries nearly always identify the people of the village (ahl) with one particular clan. In the minority of villages where the population is clan-less, the entry identifies the Arab clan that holds the protection rights.

Map: Tribes and clans

Water Rights

Most villages were irrigated by gravity-fed canals and were allocated ‘water rights’, effectively a water quota, determined by the width of the weir at the head of a local feeder canal. Some villages were fed by more than one canal, and then al-Nābulusī lists the water rights for each of these canals separately.

The width of the opening of the weir at the head of the feeder canal was measured in units called qabḍa, literally ‘fist-length’ (approximately 10 cm). A qabḍa unit may have also taken into account the slope of the canal or its depth.[4] The water quota of an individual village was taken out of the total water quota of the main branch canal for the surrounding area.

Where a main canal branched off to several feeder canals, each governed by a separate weir, the cluster of weirs was called a divider (maqsam, pl. maqāsim). These dividers were found only on the Grand Canal and major branch canals, called the baḥrs.

Villages outside of the Fayyum depression itself, mostly north and south of the al-Lāhūn dam, were irrigated in the ‘manner of the Lower Egypt (al-rīf)’, that is, by basin irrigation. Villages irrigated by basin irrigation did not have a water quota.[5]

Some villages irrigated by gravity-fed canals also did not have a water quota. This was particularly true for villages lying on higher ground, because the flow in their feeder canal was considered to be too weak and there was no need to regulate it.

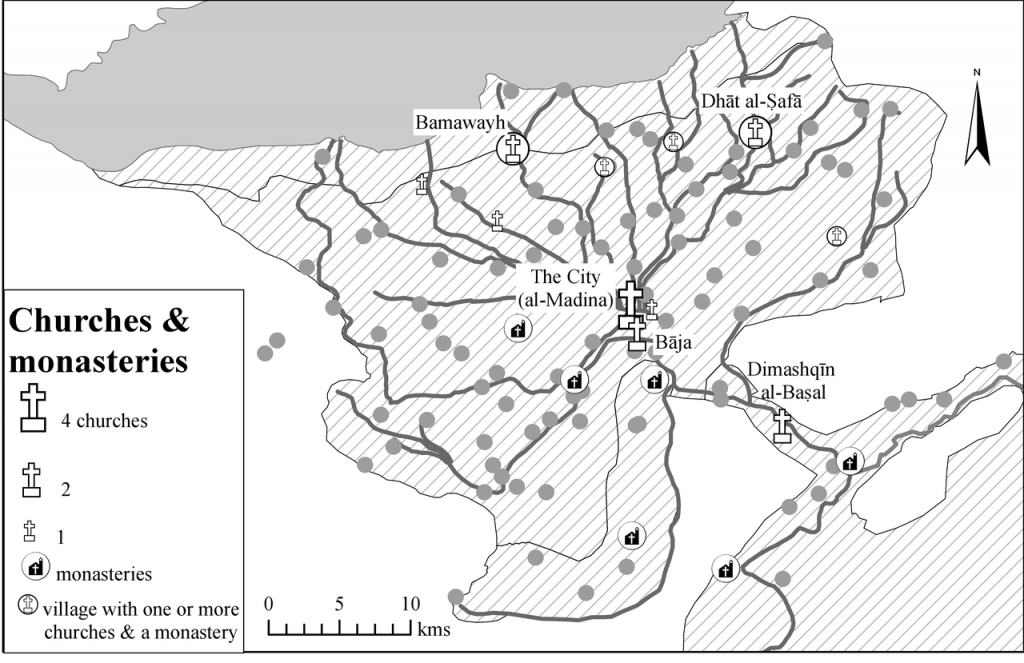

Religious Buildings

Al-Nābulusī relied on a record of churches, monasteries, and mosques in the Fayyum held in Cairo by the Ministry of Endowments of Congregational and Neighbourhood Mosques (Dīwān Aḥbās al-Jawāmiʿ wa’l-Masājid), usually abbreviated to the Ministry of Endowments.[6] Al-Nābulusī also notes the existence of some unregistered mosques not on the Ministry’s list, usually in smaller villages or hamlets.

Map: Active churches and monasteries

[1] Here we differ from Sato, who identifies the balda as the administrative unit for the iqṭāʿ: Sato, State and Rural Society, p. 179.

[2] Later, in 1315, the collection of the poll-tax was handed over to the iqṭāʿ-holders: see Rabie, The Financial System, p. 41; Sato, State and Rural Society, pp. 68, 148.

[3] Ibn Mammātī, Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. by ʿAṭiya, p. 369; al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ, iii, 442–43; Sato, State and Rural Society, pp. 153–55; Rabie, The Financial System, p. 47; Cooper, ‘Ibn Mammati’s Rules’, pp. 364–67. Stuart Borsch adopts the 1:3 ratio mentioned by al-Qalqashandī: Borsch, The Black Death in Egypt and England: A Comparative Study (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), pp. 67–90.

[4] A reference to ‘small qabḍas’ (qubaḍ ṣighār, in Būr Sīnarū) suggests that the unit was not uniform.

[5] These are Bandīq and Dimūh al-Dāthir. See also the discussion by John Ball, Contributions to the Geography of Egypt (Cairo: The Government Press, 1939), p. 220.

[6] This ministry had much discretion over the appointment and reimbursement of religious officials, such as scholars, Qur’an readers and imams. See al-Nābulusī, Lumaʿ, ed. by Becker and Cahen, pp. 25–27.