Mira Siegelberg at the Planetary Futures Seminar Series

What is the future of the planet? Whether the impending ecological crisis, the movement of hegemonic ideological socio-political realms or the techno-scientific promises of life on mars, Planetary Futures engages a broad range of disciplines. This seminar series will generate dialogue across disciplines and we invite participation from all who have interest in the planetary, whether as a scale of inquiry or an object of study. The talks will be of interest to those in the social sciences, particularly Anthropology, Sociology, History, Politics, STS, Geography as well as the Sciences, particularly Physics, Astronomy, Geology and Space Science. The goal is also to spur a reflection among the broader interested public on the construction of planetary imaginaries and interrogate our current academic apparatus for thinking about planetary futures.

More details can be found at this website.

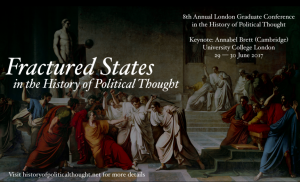

8th Annual London Graduate Conference in the History of Political Thought

Registration for the 8th Annual London Graduate Conference in the History of Political Thought is now open. Please visit the conference website for programme, registration and further details.

Georgios Varouxakis at the Université Paul Valéry – Montpellier

Richard Bourke at the University of Vienna

Since democracy is a creation of human culture, it must in some sense have been “invented”. This does not mean that the process of invention was deliberate. Instead it was a fortuitous product of human struggle. However, unlike many other political values and practices, democracy was not invented just once, but twice. This lecture is concerned with the relationship between these two moments, between the original formation of ancient democracy and its subsequent renaissance in modern history. Both events are shrouded in obscurity. First of all there is no record marking its first establishment in Athens. As a result, historians disagree about when it came into being. Then, secondly, the circumstances of its rebirth in the Enlightenment are no less complex, spawning controversy about when modern democracy began. One fundamental reason for the uncertainty is that the relationship between the ancient regime form and its modern re-incarnation has rarely been systematically explored. My argument is that a clearer understanding of what modern democracy took from its ancient predecessor can clarify how the modern version was brought into existence, and how it came in due course to be transformed.