Letter Collections and Quantitative Network Analysis

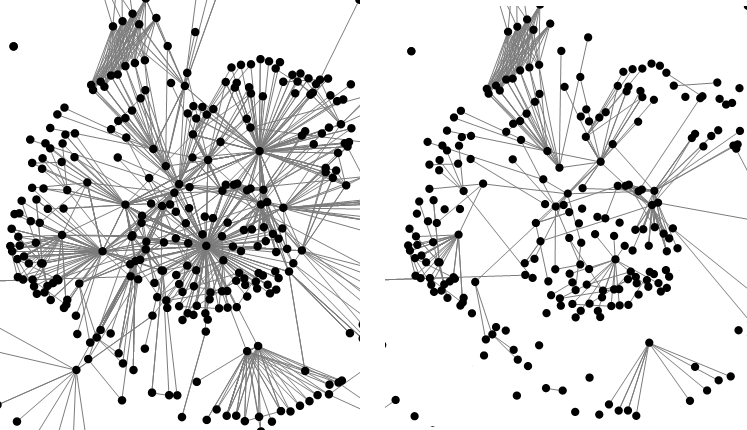

Figure: The entire letter network up to 28 July 1558 (left), and the letter network of those individuals that were still alive on 28 July 1558 (right).

Mary I of England is famed for her persecution of the Protestant church. During her short reign (1553-1558) at least 284 ‘heretics’ were burnt to death. A collaborative project led by Ruth Ahnert (Department of English, Queen Mary) and Sebastian Ahnert (Department of Physics, University of Cambridge) has sought to understand what a community does when it is placed under systematic attack. They used quantitative network analysis to analyse the body of 289 letters left behind by the leaders of the Protestant community in England, many of whom were later martyred. By stripping these letters back to simple metadata (identities of senders and recipients, dates of composition, and reported social links), the team were able to partially reconstruct the social and textual organization of this dissident community, which comprises 377 actors (nodes), and 795 social interactions (edges). By analyzing the topological properties of this network they observed both expected patterns – that martyrs are central to the organization of this community – and some surprising facts: that letter carriers and financial sustainers were more significant than we may have previously suspected. Ruth writes:

The influence of a node within a social network is typically quantified by measuring its centrality. Betweenness centrality quantifies the number of times a specific node lies on a shortest path between two other nodes, which allows us to think about the routes Protestant communications took. The top 20 nodes by this measure are mostly predictable: 14/20 are martyrs; another is a leader of the separatist group known as the Freewillers. But it also highlights Anne Smith, Barthram Calthorpe, William Bowyer, Augustine Bernher, and Margery Cooke – figures almost entirely absent from historical accounts of the Marian persecutions. Significantly, these figures occupy similar roles in their relationship to the celebrated martyrs of the Marian reign, funneling letters, goods, and oral messages between prisoners and communities elsewhere in England. Bernher was a valuable letter courier, and Cooke was one of a group of (mostly female) financial sustainers, who sent Protestant prisoners money, clothes, food, and other means of physical and emotional support. […]

The significance of couriers and sustainers becomes more marked as Mary I’s reign progresses. Studies have shown that one of the most effective ways to fragment a network is to remove nodes with the highest betweenness. The underground Protestant community in the reign of Mary I was placed under systematic attack by the authorities. Through the program of burnings, 14 of the top 20 nodes for betweenness were removed between Mary I’s accession and the end of July 1558. If we compare the complete network with the network that remains after this date (Fig. 1), it is clear that the executions had a devastating effect on the shape of the Protestant community; but, crucially, the network does not fragment. This is because the network retains its infrastructural backbone: we are left with a network in which sustainers and couriers (Bernher, Cooke and one William Punt) have the highest betweenness. Bernher and Punt seem to have taken on increasingly important roles as leaders died, themselves providing leadership within the underground London congregation.

By applying network analysis to the study of this important letter collection, this research provides an alternative view of Reformation history. Martyrs have dominated the history of the Protestant church, from contemporary accounts of the Marian persecution through to modern scholarship. By contrast, this work shows that scholars should not underestimate the role of apparently minor figures in the maintenance of the faith during this period of intense persecution. As such, it offers a hypothesis about the organization and structure of underground communities, from persecuted minorities to terror cells: that their success and longevity depends upon infrastructural figures.

On Ruth and Sebastian’s collaborative work see:

Ruth Ahnert and Sebastian E. Ahnert, ‘Protestant Letters Networks in the Reign of Mary I: A Quantitative Approach’, English Literary History (forthcoming, early 2015)

Ruth Ahnert and Sebastian Ahnert, ‘A Community Under Attack: Protestant Letter Networks in the Reign of Mary I’, Leonardo 47 (2014), 275

Ruth Ahnert, ‘Maps Versus Networks’, in News Networks in Early Modern Europe, ed. Noah Moxham and Joad Raymond (Brill, forthcoming in 2015)

They are currently working on a new project, which will analyse the 132,000 letters collected within the archive of Tudor State Papers (accessed via State Papers Online). This will lead to a book and online resource provisionally entitled ‘Tudor Networks of Power’.