CEREES in east London

A ‘Little Russian Island’ in London’s East End

Robert Henderson

Exploring ‘the Russian East End’

East London’s migrant communities and the radical émigrés that fled tsarist persecution

Revolutionary meeting spots, from Whitechapel to Mile End Road and the People’s Palace

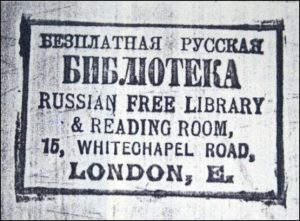

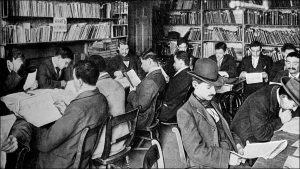

In a 1902 report to his superiors, one French security service agent, writing from London, claimed that the main Russian political émigré association in England was located in London’s East End. The ‘Whitechapel Group’ as he called it, had its headquarters in a cramped library, in Church Lane, which served as the ‘rallying centre of the Russian revolutionary movement in London’. According to the agent, the group’s members were mainly Jews who had fled Russia and Poland to escape military service. It was here, thanks to the radical literature put at their disposal in the library, that their political education was completed and they became fully-fledged revolutionaries. The agent went on to describe the founder-manager of the library, Aleksey L’vovich Teplov, as ‘one of the most influential members of the revolutionary party here’. [i]

Teplov had opened the doors of his Free Russian Library (Russkaya besplatnaya biblioteka) for the first time some four years earlier, and since then had seen it grow to become much more than a simple reading room and lending library. Not only did it assume the role of reception centre and employment exchange for new arrivals from the Russia Empire, but it also came to serve as the social, political and cultural hub of the ‘Russian East End’.

Teplov had been actively involved in spreading socialist propaganda amongst railway workers in the Russian provinces until his arrest and exile to Siberia. As the crackdown on political opposition of any kind widened, he and many of his associates were obliged to flee. Much later, having settled in Whitechapel, the revolutionary determined to renew his work in raising the political consciousness of the burgeoning community of East European Jewish immigrant workers he found there.

‘That area of Whitechapel between Mile End Road and Commercial Road was later named the “Little Russian Island”.’

Although the East End had already served as a place of sanctuary for Polish Jews escaping Russian persecution in the 1860s and 1870s, it was the 1880s and 1890s that witnessed the largest influx of immigrants form the region. This had been triggered by the 1881 assassination of Tsar Alexander II and the ensuing rumours that Jewish revolutionaries had been responsible for the murder. This led to a series of vicious pogroms in Ukraine and elsewhere, as well as to the passing of a number of anti-Jewish laws. Forced to abandon their homeland, many of the refugees found their way as far as the Port of London.

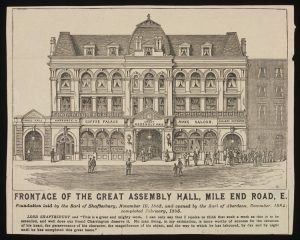

Some would then continue their journey onwards, to one of the other large British cities or to America. The majority, however, were content to settle where they had landed and, with the assistance of such charities as the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter at 84 Leman Street, to find work and accommodation with their compatriots and co-religionists in Whitechapel. In Britain, at this time, there was a great deal of sympathy for their plight—with one particularly large rally being held at the Great Assembly Hall, on Mile End Road, to protest at their persecution.

That area of Whitechapel between Mile End Road and Commercial Road was later named the ‘Little Russian Island’ (russky ostrovok) by the Russian revolutionary Apollinariya Yakubova in her reminiscence of her years spent working with Teplov in his Free Library. The term ‘island’ was an appropriate one, indicating the ‘separateness’ of this community. Many commentators, such as Charles Booth, echoed that description, pointing to the way the East-End Jews ‘live and crowd together and work and meet their fate independent of the great stream of London life surging around them.’[ii] That distinctive quality of the colony was described by Conservative M. P. Major Evans Gordon (no friend of immigrants of any nationality), simply and bluntly, thus: ‘East of Aldgate one walks into a foreign town.’[iii] Indeed, by the early years of the 20th century, the Russian and Polish population of the borough of Stepney alone numbered more than 40,000.[iv] It was only natural therefore that public facilities should cater for that constituency. In a matter of a few years Whitechapel was strewn with businesses providing goods and services specifically for Russian and other East European tastes: shops, restaurants, synagogues, schools, music halls, post-offices, bath-houses, all were to be found there. Then, of course, there was Teplov’s library, followed shortly thereafter by another of the revolutionary’s educational enterprises.

‘Regular lectures … by some notable visitors to the capital, such as Julius Martov, Lev Trotsky, and Vladimir Lenin himself’

Following on from the Free Library’s success, Teplov and his colleagues set about organizing a series of public lectures. Speakers included such notables as Nikolai Chaikovsky, David Soskice and the recently arrived Konstantin Takhtarev and his wife Apollinariya Yakubova. The lectures, both political and non-political, proved so popular, it was decided to organise them on a more formalized basis. And so it was that, in early 1902, the East End Socialist Lecturers’ Society (Sotsialisticheskoe lektorskoe obshchestvo v Ist-Ende) was founded. Yakubova took on the role of both secretary and treasurer and became the driving force behind the Society.[v]

A permanent home was found for the venture—the aptly named Liberty Hall, at 9 Pelham Street, just off Brick Lane. Regular lectures on a range of topics were held there on Fridays and Sundays, and, over the first eighteen months, an impressive total of more than 120 lectures were delivered both by members of the local émigré community and by some notable visitors to the capital, such as Julius Martov, Lev Trotsky, and Vladimir Lenin himself. In November 1902, the latter delivered a speech to a packed hall on the topic ‘The Program and Tactics of the Socialists-Revolutionaries’.[vi] Indeed, Lenin was no stranger to the ‘island’. On an earlier occasion he had arrived unexpectedly at Liberty Hall and there gave a personal account of his newspaper’s programme to a small Social Democratic workers’ circle that habitually gathered there.[vii] It is also known that he visited Toynbee Hall, around the corner on Commercial Street, to attend a debate on ‘Our Foreign Policy’.

It should come as no surprise that such a hive of political activity would attract the attention not only of the French Sûreté, but also of other security services. The Whitechapel revolutionaries were perfectly aware that they were under constant surveillance not only by Scotland Yard, but also by the okhrana. The Sûreté’s London agent sent regular reports on the émigrés’ activities to his superiors based in the Russian Embassy, in Paris. On one occasion, he even claimed to have infiltrated the Free Library with one of his own men.[viii]

The inhabitants of the Little Russian Island, however, paid little heed to the spies in their midst, and may well have continued with their political preparations were it not for the revolutionary events of 1905. With the publication of the tsar’s October Manifesto and the subsequent declaration of an amnesty for certain political refugees, many in the Russian East End smelled the scent of victory in the air and made plans for an immediate return to their homeland. Teplov, however, together with a few others, stayed behind. His library would continue to serve what remained of the community in the East End, but numbers were destined to fall.

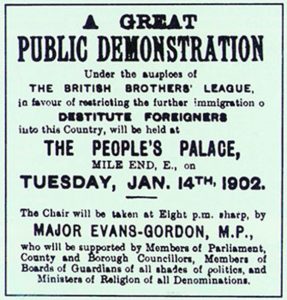

In Britain, opposition to East European immigration had been on the increase for a number of years. In 1902, Evans-Gordon and his followers in the proto-fascist British Brothers league had staged a provocative rally in the very heart of the East End at the People’s Palace, Mile End Road calling for the restriction of further immigration of what they termed ‘destitute foreigners’. The subsequent passing in parliament of the 1905 Aliens Act marked the beginning of a lengthy period of depopulation in the East End. Numerous traders being obliged to close down due to diminishing numbers of customers, while those families lucky enough to afford it, relocated home and business to more affluent Jewish areas of the capital.

Today, sadly, should one take a walk through the streets of the East End one will find scarcely a trace of that vibrant East European Jewish community to whom the area served as a place of refuge and home for upwards of thirty years. There is, however, one small monument still to be found. It stands in the very heart of the East End on the Whitechapel Road directly opposite the main entrance to the Royal London Hospital. It is the King Edward VII Jewish Drinking Fountain erected in 1912 “from subscriptions raised from Jewish inhabitants of East London” in memory of the late King and in gratitude to the local community for their earlier hospitality.

ENDNOTES:

[i] Archives nationales, Paris (AN), F/7/12521/2: Angleterre (1887–1908), Reports for 21 January, 28 February, and 15 March 1902. Other political associations mentioned were the Hammersmith Group which included those associated with the Russian Free Press Fund and Chertkov’s Tolstoyan colony in Christchurch.

[ii] Booth, C. (ed.) Life and Labour of the People of London (1892), 1, 581. (Cited in A. Palmer. The East End: Four Centuries of London Life. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2000, 103.)

[iii] Evans Gordon, W. The Alien Immigrant, London: W. Heinemann, 1903. (Cited in Palmer, op. cit. 104.) The previous year he had chaired a meeting at the People’s Palace, Mile End Road, calling for the restriction on immigration of “destitute foreigners”.

[iv] Lipman, V. D. Social History of the Jews in England, 1850—1950. London: Watts & Co., 1954, 94.

[v] Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv rossiiskoi federatsii (GARF) f. 1721, op. 1, ed. khr. 56, ll. 63,64..

[vi] Rothstein, Andrew. Lenin in Britain. London: Communist Party of Great Britain, 1970. 14.

[vii] Mikhailov,I. K. Chetvert´ veka, podpol´shchika. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel´stvo politicheskoi literatury, 1957. 88.

[viii] Hoover Institution Archive, Okhrana Archive, 54/VI/k/23 c. 20 September 1905.

Author:

Robert Henderson gained an MA in Russian and a Diploma in Slavonic Languages at the University of Glasgow before taking up the post of Russian Curator at the British Library. Some twenty years later he returned to academic studies in the School of History, Queen Mary University of London, and in 2009 completed his doctoral research into the Russian political emigration in late nineteenth century London. He has published extensively in that field, the latest being the monographs: Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia: A Revolutionary in the Time of Tsarism and Bolshevism (Bloomsbury) and The Spark that Lit the Revolution: Young Lenin in London and the Politics that Changed the World (Bloomsbury). Dr Henderson is an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of History and an Affiliate of CEREES at QMUL. He is a part of the CEREES in east London Research Group.