From Sir Mix-A-Lot to Fergie to Nicki Minaj, big butts have become a metaphor for female hypersexuality. Media images of women with curvaceous behinds have become the norm, and under the reign of the Kardashian social media empire there is no escaping the fact that a large booty (best captured in a ‘Belfie’) means attention, likes and favourites. But where does this fascination stem from? Have women always been adored and celebrated for looking this way? Nineties supermodels who were the fashion and body icons of their time were notoriously stick-thin, with smaller chests and almost non-existent behinds in comparison to today’s standards. Therefore, some people might be surprised to learn that western culture has been in awe of the big booty for centuries…

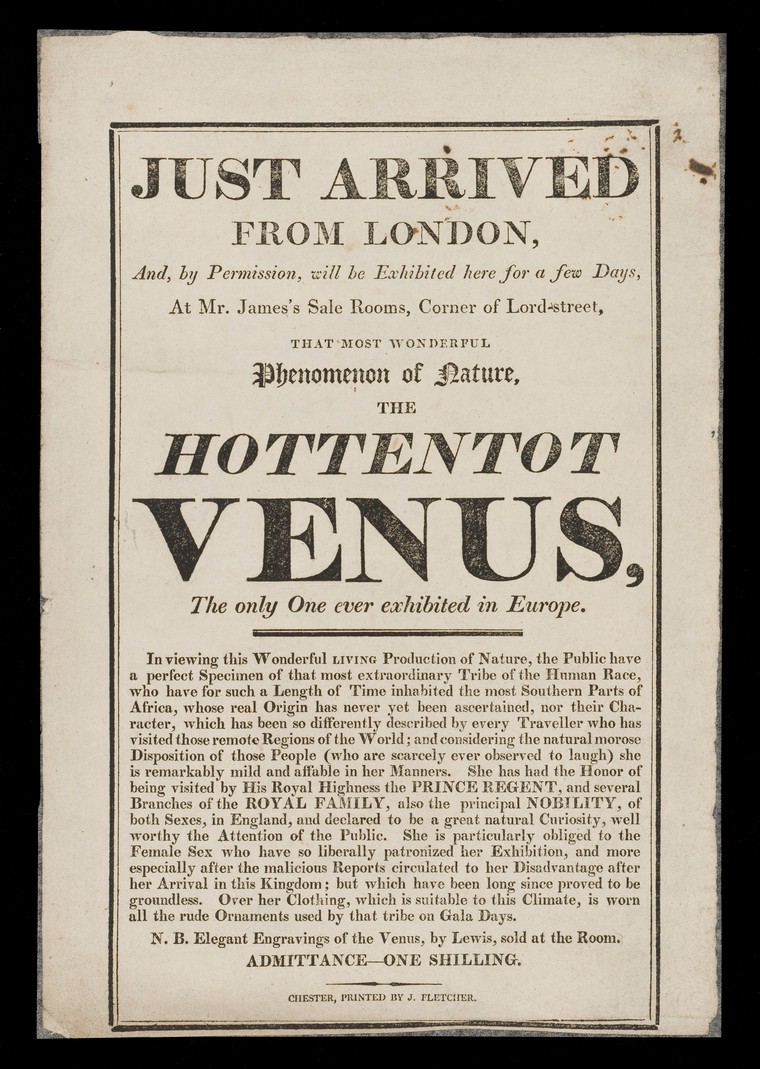

‘The Hottentot Venus’ – real name Sara or Saartjie Baartman – was a woman of indigenous South African descent originating from the Khoekhoe tribe, and she soared to fame for her bodily assets. When she arrived in London in 1811, Baartman was described by Alexander Dunlop, the man who touted her body to freak shows and fairs, as a woman of ‘extraordinary shape and make … and an object of great curiosity’. Her large bottom was central to her identity as a woman of Khoekhoe origin (the result of a condition called steatopygia), but Dunlop saw a moneymaking opportunity in the young woman. He chose to exhibit her as a primitive woman, when she had in fact lived out most of her life under British colonial rule in Cape Town. Interestingly, as Baartman began to assimilate herself into the culture of London life, the less exciting she was to western patrons. Posters for her shows depicted her in native dress, and she would wear a brown slip dress to hint at her naked form. British and French men and women would gather at 225 Piccadilly and the Palais Royal to watch Baartman dance and sing in her native language, and were even encouraged to touch her bottom to ensure its legitimacy.

There are inevitable questions about Baartman’s consent regarding these shows, as well as whether or not she was given a share of the profits, and if her status as a free black in the United Kingdom was recognised. She was the object of public fascination for the four years in which she performed as the Hottentot Venus. But many have forgotten Sara Baartman, and only recently has her story come to wider attention following the repatriation of her remains to South Africa in 2002.

After her death in 1815, French natural scientist Georges Cuvier obtained the corpse of Baartman for dissection purposes. He dissected her genitalia and preserved it along with her brain, as well as separating her skeleton from her flesh and making a cast of her naked body to be displayed in the Mussée de l’Homme. In doing so, Cuvier immortalised the Hottentot Venus as a monument to the racial differences between the Khoekhoe people that he described as closest in resemblance to the ape, and the Caucasian people who gawked and prodded at Baartman during her shows. In her lifetime Baartman had exercised some level of agency over her own body, but in her death she was a foreigner, concealed in a glass cage where she could remain an object of fascination for the continuing thrill and intrigue of western society.

In today’s music culture, big behinds are a commodity, something to be desired. Kim Kardashian’s husband Kanye West raps on his newest album ‘I’m the ghetto Oprah … You get a fur! … You get a jet! … Big booty bitch for you!’, suggesting that being with a woman who possesses such an asset is parallel to owning a private jet. We can see from this how the gaze has changed over the centuries, with the big bottom evolving from being something freakish to a situation where people are celebrating women with large bottoms. What has transformed the nineteenth-century fascination-verging-on-repulsion into twentieth-century desirability?

In recent years several critics have accused the Kardashian empire of adapting and manipulating historically black culture, monetising it by integrating it into their personal brand. Combined with money and power, it is argued that the Kardashians have increased the attraction of black culture that has historically been shunned. Kim Kardashian herself is no stranger to cultural appropriation and has been critiqued for wearing what she called ‘Bo Derek braids’, when in fact the hairstyle is a native African tradition called ‘Fulani braids’. The black community, especially those prominent in the social media world, have called out Kardashian for adapting elements of black culture and profiting from or hypersexualising them.

It is interesting that the name Sara Baartman might mean nothing to many of the people who are swept up in the cult of the Kardashians. This is why it’s important to understand the social developments that have occurred over the past 200 years with regards to black culture, black bodies and especially black female bodies. Globalisation and celebrity culture mean that parts of all cultures have inspired fashion and beauty trends over the last two centuries, and it is imperative to be aware of these cultural ‘borrowings’. In a case such as Baartman’s – subjected to scrutiny in life and injustice in death – not to acknowledge her place in the history of the way that western society has viewed and voiced its opinions on black women’s bodies, would be an injustice in itself.

Further reading

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/kim-kardashian-bo-derek-braids-new-hairstyle-braided-cultural-appropriation-snapchat-instagram-a8184801.html

Clifton C. Crais and Pamela Scully, Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography, Princeton University Press (2009).

I want to learn more as a multi-ethnic woman I need to understand my place in the community of great women everywhere.