Readers who have been watching the ITV series Broadchurch will be familiar with the story of Trish Winterman, who suffers a rape at a party by an unknown assailant. Broadchurch has been notable in its foregrounding of the emotional experiences of Trish, managing to depict the stark realities of rape without crossing over into sensationalism. Trish’s story has captured viewer’s attention and, by offering such a frank depiction of rape in a prime-time TV slot, has presented an opportunity for further discussion about a serious crime. It is not the first time that TV has made such an attempt to address the realities of rape; a key phenomenon that I’ve been looking at lately was something hailing from America: the made-for-TV movie.

The 1970s was the golden age of the TV movie, a network-produced film that used existing network producers and directors, and thus got around the issue of paying high prices to major studios to broadcast their products. Despite their lack of Hollywood credentials, made-for-TV movies were a hit with domestic audiences: in 1974, 130 new TV movies were aired in America. The large number being produced reflected the fact that many had a limited shelf life; they relied on current and newsworthy topics for their success. The popularity of the format in the 1970s coincided with a renewed focus on crime in the United States, as well as second-wave feminism. Tackling rape was high on the agenda of institutions like the National Center for the Prevention and Control of Rape, with significant efforts being made to debunk rape myths and highlight the pervasiveness of victim-blaming in the legal system. These discussions about rape were readily incorporated into the TV movie.

TV movies were explicitly geared towards a female audience, placed in evening slots that capitalised upon housewives’ free time. There was something uncanny about many of these movies in the way that they mirrored the lives of their audience. Their basic plots tended to revolve around some form of disruption to suburban domestic life. Many relied upon a ‘woman-in-peril’ motif to capture the attention of their audience – such as Victims for Victims, in which actress Theresa Saldana played herself in a dramatization of her attempted murder by a fan. The use of a personal story to explore wider social or legal problems appealed to viewers on an emotional level, but also resonated with second-wave feminism’s message that ‘the personal was political’.

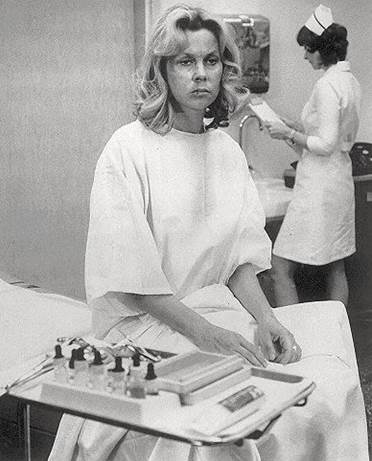

The stark realities of the aftermath of rape (A Case of Rape, Universal Television, 1974. Still: Jennifer Wallis).

One of the most successful of all TV movies was A Case of Rape, aired in 1974 by NBC. Starring Elizabeth Montgomery (of Bewitched fame) as middle-class housewife Ellen, the film aimed to address a number of rape myths, but could be argued to have perpetuated just as many. Ellen is a wife and mother, and it is the impact of rape on those around her – more so than Ellen herself – that forms the crux of the film. Ellen’s independence – her attendance at evening classes and socialising with her male classmates – perpetuates the myth that she has somehow brought the rape on herself. In attempting to report the rape immediately, Ellen is dissuaded by the aggressive manner of the police officer on the phone; it is only when she is raped for a second time by the same man that she is moved to report it. This heralds the beginning of a set of painful personal and legal battles. Ellen is interrogated by police who ask whether she found the idea of force exciting, and her husband becomes suspicious of her complicity in the act given that she didn’t report the first rape, also blaming her for the impact on the couple’s sex life.

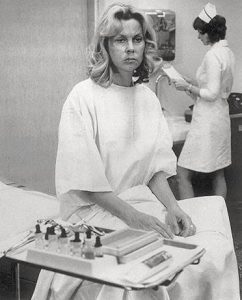

Ellen (Elizabeth Montgomery) testifies against her rapist (A Case of Rape, Universal Television, 1974. Still: Jennifer Wallis)

Given its sustained focus on the legal team’s efforts to get Ellen’s rapist convicted, A Case of Rape offers a jarring conclusion to the audience: her rapist is found not guilty. The police say that some of the laws they are working with are outdated and “don’t make much sense anymore”, while Ellen’s lawyer bemoans poorly-educated and prejudiced juries. A Case of Rape clearly positioned itself as a reflection of contemporary experience. The opening credits of the film recite statistics on rape, and the epilogue adds a similarly pseudo-factual air with its report that Ellen’s rapist was caught fleeing the scene of another assault shortly afterwards.

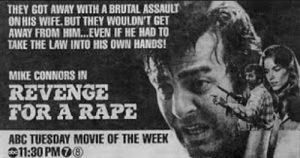

Advertisement for Revenge for a Rape (Albert S. Ruddy Productions, 1976). Used with thanks to Amanda Reyes.

One of the things that I find so interesting about these movies is how they explicitly attempt to engage with current social issues but often end up perpetuating some of the myths they try to deconstruct. They often also reduce their female leads to mere plot devices. Revenge for a Rape (1976) is a good example of this, in which a woman’s rape serves as the rationale for a Death Wish-inspired chase movie as her husband hunts down the suspects. In a startling twist, it is finally revealed that he has chased (and killed) the wrong men, because his wife had – while traumatised – made a misidentification. Revenge for a Rape, as well as pushing the victim into the background, also manages to suggest that women’s testimony is unreliable and untrustworthy.

Many TV movies found it difficult to offer a satisfactory conclusion to their viewers. In contrast to rape-revenge feature films like I Spit On Your Grave (1978), which foregrounded female power and bloody retribution, TV movies worked within a more conservative structure. Their messages were affected by network guidelines about appropriate content as well as strict time constraints that confined the movie to around 90 minutes. But the pessimistic outlook presented by many TV movies was also a direct result of their aim: to present realistic, rather than idealised, pictures of the topics at hand. Many networks broadcasted helpline numbers during advertisement breaks, positioning the TV movie as a form of therapeutic space. Although legal developments and media attention suggested positive changes to rape laws in the 1970s, it was also a period of transition as the courts, police, media, and the public got to grips with new conceptions of, and language surrounding, sexual assault and rape. In this sense, the TV movie’s lack of optimistic conclusion in relation to rape plots (the capture and imprisonment of the rapist) is less surprising. By presenting stories of women whose lives were shattered by sexual assault, and of rapists escaping justice, the TV movie – like recent episodes of Broadchurch – well portrayed the realities faced by many rape victims and highlighted the challenges facing contemporary legal and social reformers.