Man Up – The Victorian Origins of Toxic Masculinity

The latest figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) once again confirmed that men are three times more likely to commit suicide than women. Suicide remains the single biggest killer of men under the age of 45 in the UK. The lack of improvement in these figures has been combatted in recent years by specific campaigns, run by charities such as CALM, to challenge social stigmatisation of mental illness particularly for men, and offer support to those in crisis. The culture of toxic masculinity that modern society prescribes – one of a variety of models available to men – in which men have to be unemotional, strong, sexually dominant and violent, is clearly harmful to women and those in the LGBT+ community, but evidently it is also deeply damaging to men. In fact, it is literally killing them.

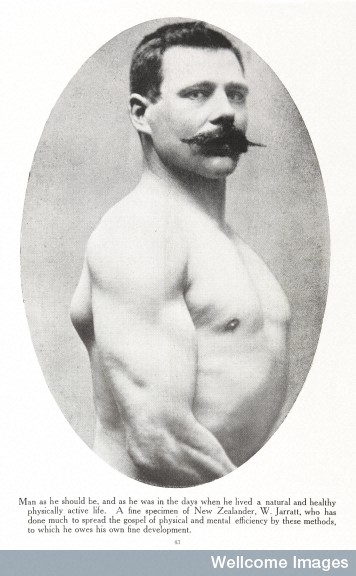

L0034500 W. Jarratt, Man as he should be, and as he was

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

License: CC BY 4.0

Damaging ideals of manhood, however, should not be understood as a purely modern phenomenon. Many of the characteristics that toxic masculinity prescribes in the twenty-first century, and those which contribute to the stigma surrounding men discussing their emotions and more seriously their mental health, can be traced back to the Victorian period. In the late nineteenth century, changing ideals of masculinity gave way to the dangerous expectations that still hold sway today.

Broadly, Victorian masculinity can be outlined as an ideology of spirituality and earnestness between 1837 and 1870, that changed to one of strength and stoicism from 1870. The ideas prevalent in the second half of this period can be understood as the foundations of a modern culture in which men are dying.

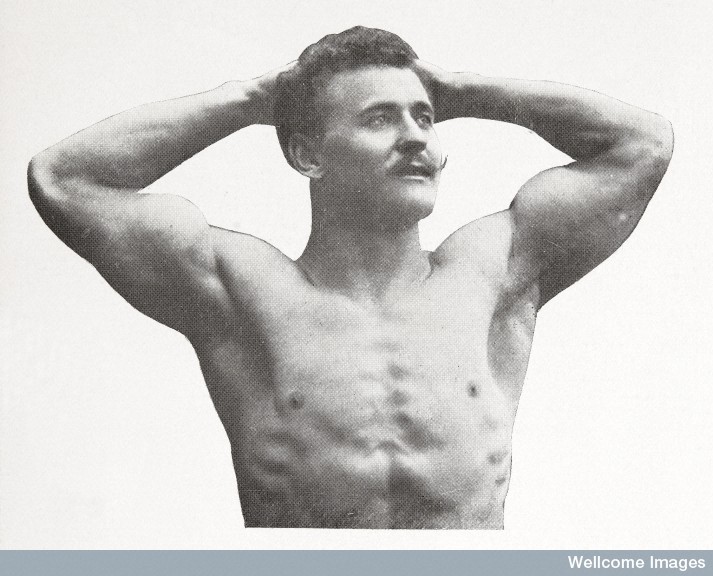

Bodybuilder Eugen Sandow

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk

License: CC BY 4.0

Strength and athleticism were vital aspects of Victorian masculinity, as today. In the twenty-first century, this often takes the form of unrealistic expectations of the male body, as exemplified in the ever popular superhero film, which reflects a wider expectation of emotional strength. Physical strength in the Victorian era, however, took several forms. The first was the games-worshipping of the late nineteenth century. Between 1860 and 1880, games-playing was made compulsory in English public schools, where boys could demonstrate their physicality, and thus manliness, from an early age. In addition, manliness combined with religion in the phenomenon of muscular Christianity, commonly found in the writings of authors such as Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. The hyper-masculinity of the late Victorian period was not at odds with other dominant cultural forces in the era.

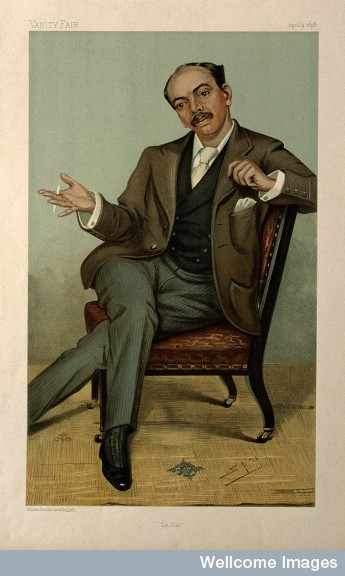

Physical rigour was needed for men to be fit enough to fight and defend the British Empire. Late Victorian ideals of manhood as war-ready are evident in the literature of the time. To take one example, Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘If…’ (1895), which acts as a guide to manhood for his son, takes inspiration from colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson, presenting him as the ideal man. One characteristic which the poem promotes is that of level-headedness or stoicism suggested, for example, in the first two lines: ‘If you can keep your head when all about you/ Are losing theirs and blaming it on you’. Although imperialism is of little significance today, ideas of stoicism still endure. It is a widely-held notion that boys don’t cry and men are often depicted as rational and unemotional. And it is this set of beliefs which undoubtedly contributes to the higher rate of suicide among men today.

Sir Leander Starr Jameson. Colour lithograph by Sir L. Ward

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

License: CC BY 4.0

It is interesting to consider the motivation behind the cultural ideals surrounding masculinity, specifically whether the promotion of strength, virility and stoicism were, and are, in reaction to new ideas about the place and position of women in society. Both the late nineteenth century and the twenty first century have seen the promotion of greater equality for women and the challenging of traditional gender roles. In the late Victorian era, this manifested itself in the so-called flight from domesticity, which saw men delaying marriage or not marrying at all, and often vehement anti-suffrage campaigns.

2017 has already witnessed women passionately campaigning in the global Women’s March in January, and on International Women’s Day in March; perhaps the toxic masculinity that prescribes such damaging ideals to men is a reaction. Men have only recently begun to be studied as gendered beings within history and it is clear it is important to continue to scrutinise cultural expectation of masculinity in the modern day.