What was the earliest example you found of self-harm, and which was the most surprising?

People have inflicted injuries on their own bodies throughout history. It’s important to realise, however, that this has not always been viewed as self-harm, which is a relatively recent category. It was in the Victorian era that people first considered that there might be relevance in grouping together what, on the face of it, seem to be very different kinds of acts, from skin-picking to self-amputation.

The religious sect of flagellants in medieval Europe, for example, were considered problematic not because they whipped themselves (which was accepted as a religious practice), but because they did so as part of a very public group ritual. The flagellants were mostly ordinary believers, not clerics, and included people from a mix of social backgrounds. Some groups even admitted women as well as men. This made them appear to be a threat to the hierarchy of the church, and the practice was banned by the Pope in 1349.

A flagellant resting on a stone. Etching. Image: Wellcome Library, London.

The most surprising thing to me was the extent of discussion of self-castration in the late nineteenth century. One editorial in The Lancet went so far as to claim that there were “many well-authenticated cases of youths and men of all ages who have sometimes successfully, at others unsuccessfully, performed this painful operation upon themselves”.

No evidence was ever given to back statements like this up – and I couldn’t find any evidence of it myself in medical or asylum records – but it seems to have been widely believed at the time. Some of this was down to the power that stories often have in shaping ideas. The Lancet quote was from a commentary on the case of one particular young man, Isaac Brooks, whose attempts at self-castration were reported in national and local newspapers in early 1882. From London to Liverpool, Glasgow to Leeds, and Sheffield to Birmingham, reporters speculated on the life, habits and personality of this ordinary 29-year-old stonemason and small-farmer, to try and determine why he might have twice injured his genitals. Brooks had recently died, and no conclusive answer was ever found, but this didn’t stop the regular updates on the story, ensuring that castration was thought by many to be the ‘main’ kind of self-injury at this time.

Was it difficult to decide what should be included in your category of “self-harm” – for instance, including religiously motivated self-castration along with what readers might consider more obvious modern examples?

My book is essentially a history of psychiatry, so I looked at the way categories of self-harm or self-injury emerged in a medical context, and how these have varied in different periods. My main decisions about what to include were shaped by the clinicians I was working on – Karl Menninger in the 1930s, for example, considered nail-biting and accidental injury to be forms of self-mutilation, while James Adam in the 1880s did not. Even today there’s no widespread agreement as to what constitutes self-injury. In the United States definitions tend to exclude overdosing; in the UK this is not the case. One of my main contentions was to question the very existence of a category at all – but of course the book had to have a title, so you end up running the risk of perpetuating the thing you’re seeking to critique! It’s a tricky balance.

With the early examples – those which pre-date the first categorisation in the late nineteenth century – I wanted to get across the message that there are many other ways of considering practices that alter or damage the body than self-harm. This is often where the religious descriptions came in. Victorian psychiatrists tended to use examples of self-wounding from the bible, like the man described in Mark 5:1-13, who cut himself with stones while possessed by spirits, to prove that self-mutilation has always been a universal human impulse. But the way we view or understand something – as evidence of demonic possession, as a spiritual rite, a ritual of group bonding, a political statement or an individual pathology – changes both the experience of it and our reactions to it.

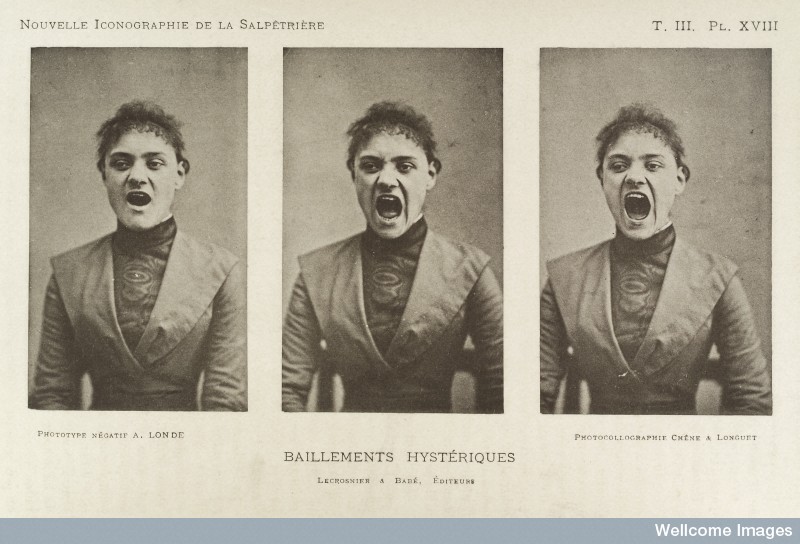

A series of three photographs by Albert Londe showing a “hysterical yawning woman”, c. 1890. Image: Wellcome Library, London.

There’s been a lot of media interest in your book and I wonder how you’ve found that. What was it like going on BBC Radio 4 ‘Woman’s Hour’ for instance?

The short answer? Absolutely terrifying! My main fear was that I wouldn’t manage to get what I wanted to across live on air. On a personal level, it was also the first time I’d ever really spoken in public about my own experiences of mental ill-health. Thankfully, my appearance on Woman’s Hour was much more relaxed than I expected. I’d never been on radio before, so I hadn’t considered the fact that I wouldn’t really be able to tell that I was being listened to live – it’s not like having a TV camera in your face, after all. When you’re sitting in the studio opposite the presenter it’s more like a one-to-one conversation.

I really wanted to get across the way attitudes to self-harm have related to wider public concerns, in particular contentions about gender. Early definitions tended to focus on men, but in the twentieth century this shifted significantly, with self-injury newly understood as a manipulative or hysterical practice often associated with women. Perhaps more importantly, this understanding of self-injury was then used to support ideas about the psychology of women generally – if women self-harm, then women generally must be more deceitful than men. Looking back at these statements can be quite shocking to a modern audience but also, I think, opens our eyes to the way some of these notions remain embedded in our culture and attitudes today.

Why do you think history is important to our understanding of psychiatric categories and treatments today?

Victorian psychiatrist George Savage put it very well when he said that ‘the definition is after all but the summing up of the knowledge of to-day; it is not an absolute reflex of nature’. This summing up is in constant flux, but it’s only when we look at changes across a period of time that we recognise this. Without a historical approach, the categories of our own era can seem fixed and rigid, yet they are not immutable things.

Psychiatric categories, today and in the past, are a reflection of prevailing notions about what it means to be human: what’s normal or abnormal behaviour, and how we might measure these things. Yet the views in our own era become so closely entangled with the norms we’ve been brought up with that they can easily seem like common sense. Encountering something very, very different makes it easier to acknowledge and re-evaluate the assumptions we all make every day.

This is the main thing I hope people will take away from my book. The views of today are not necessarily the right or only way to see things, and self-harm in particular is a very questionable category.

Thank-you for sharing your thoughts, with The Historian, Sarah.

Psyche on the Skin: A History of Self-harm is available from Reaktion Books (£20) or the bookseller of your choice.