At the end of June 2024, a group of postgraduate students and early-career scholars gathered for a week in Cambridge to take part in the Hands On: Hackathon. Gladly, I was one of them. I arrived in Cambridge on Monday, around noon, excited to meet new people and to learn more about digital humanities. In retrospect, however, I could hardly imagine what I had signed up for. The weather was beautiful, and it stayed sunny and dry for the whole week – since I’ve lived in the UK, I’ve learnt not to take that for granted!

Cambridge, June 2024.

We were welcomed at the University Library by the organisers: Eyal, Mary, Chris and Suzanne. As we arrived, we had food and a fair amount of coffee – we realised quite soon that it was the most essential ingredient for a successful hackathon. It didn’t take long to realise as well how diverse the group was. There were historians, literary scholars, and researchers in cultural studies and digital humanities from four different universities (Queen Mary University, Cambridge University, Charles University in Prague, and Hebrew University in Jerusalem). There were also professional artists and software developers. A rather uncommon mixture in an academic setting, but that’s how magic happens. The variety of expertise in the room allowed us to form highly interdisciplinary teams, which soon proved to be the right path forward. Each team had to create a prototype of an app to make scientific research on manuscripts available to the broader public. The manuscripts in question were the two extant copies of the Great Bible preserved at the National Library in Wales and St John’s College in Cambridge, respectively.

Students working on their prototypes.

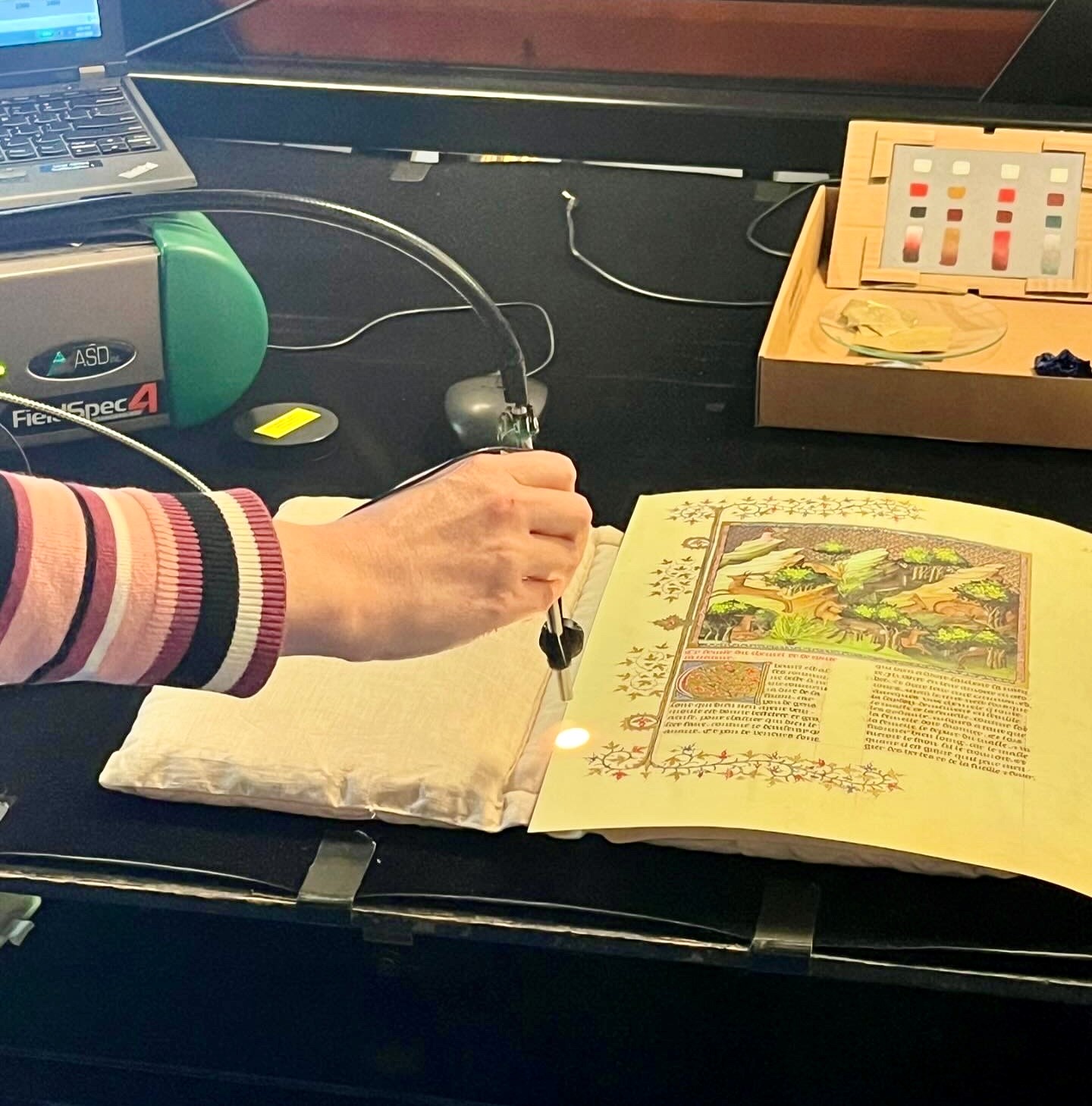

On Monday afternoon, we received an introduction to the different scientific techniques applied in manuscript studies. We also had the opportunity to meet the staff that took care of it at Cambridge University, as well as to look at the facilities where this research is carried out. It was much information in just a few hours, which set the tone for what lay ahead. The following morning, we formed small teams and began the prototype brainstorming. Each team had a software developer and plenty of academics willing to make their life difficult. I was amazed to see how creative one can get without academic pressure. We were keen on drafting our ideas on paper – no electronic devices – to create as many sketches as possible, improving them by repetition. This approach was genius, and by the end of the day all teams had a clear idea of the prototype they wanted to create.

Wednesday and Thursday passed by very quickly – time flies when one is having fun. It was a couple of days of intense teamwork to set up the prototypes, and we soon realised that turning our paper sketches into functioning apps was no easy task. There were technological challenges, for sure. Not everything that we had on paper could be done digitally; among the things that could be done, some didn’t turn out as we had envisioned them. The biggest challenge for me, however, was making the information accessible to the broader public. We were designing apps for user personas who were not academics nor familiar with the Great Bible’s manuscripts. Neither could we assume that they knew about the uses of scientific techniques in manuscripts studies.

In particular, my group was designing the app for a middle-aged person visiting a museum exhibition on holiday. The other groups were setting up apps to be used by a teenager in a history class, and by an art curator eager to learn something they could apply in their own job. Since our prototypes had to meet the interests and needs of our user personas, we needed to make decisions about the information that we wanted to include and the best way to display it. This caused engaging debates as we bonded over a shared commitment – and some occasional “despair” – to create something good.

The opportunity to bond with the other participants of the hackathon continued outside the work environment. I believe many of my colleagues would agree that this was an extraordinary group of people who got on really well from the start. We shared breakfasts and dinners, and even went to the pub on Thursday evening to watch England’s football match together. The organisers contributed to this friendly environment too. One of the most enjoyable moments of the week was when Eyal invited us all for dinner on Wednesday evening. We did a picnic outside his house. It was an excellent way to decompress over delicious homemade food, and I must say that I had the best focaccia I have ever tried.

Students at the Trinity College Library.

Another highlight was our visit to the Trinity College Library on Wednesday afternoon. We had the opportunity to take a close look at some of the manuscripts they preserve, which was incredibly special. Surprisingly, one of the hackathon’s participants had worked for a long time on one of the manuscripts that we saw. She had used a digital copy but had never seen the physical item, so she was very moved to have it in her hands.

Overall, this week in Cambridge has been a step out of our comfort zone. We left aside academic rigour to push the boundaries of our creativity. We developed new skills and collaborated to create prototypes that were both instructive and appealing to the public. But most importantly, we managed to do it all in record time – miraculously – and to still have fun!

Many thanks to the participants of this year’s edition, to the organisers Eyal Poleg (QMUL History), Mary Chester-Kadwell (Cambridge University Digital Library), Chris Sparks (QMUL History) and Suzanne Paul (Cambridge University Library), and to the institutions that co-organise the event.