When we think of medieval trade, the image that often comes to mind is that of an exotic Oriental merchant, adorned in flowing robes, trading precious goods from the East to the highest bidder. For centuries, discussions surrounding this era have been dominated by tales of luxury items – spices, silk, gemstones – as if they were the sole currency fuelling the medieval economy. But what if the true lifeblood of maritime exchange was something far more ordinary?

Imagine the bustling ports of the medieval Mediterranean, where merchant ships laden with bulk goods like grain, timber, and ceramics plied the waters, forming the backbone of regional trade networks. This is the provocative narrative proposed by historian Chris Wickham, challenging long-held assumptions about the primacy of luxury goods. His argument finds an unlikely ally in the fragrant tale of camphor, a seemingly luxurious commodity that may have straddled the line between exotic rarity and widespread demand. But hold on, you might be thinking, “Camphor? Isn’t that the stuff that grandma used to keep moths at bay?” But the reality is, back in those medieval times, camphor was no mere moth repellent – it was a luxury item, highly coveted and commanding serious respect, even envy, from merchants near and far.

Figure 2: Camphor tree – Camphor is extracted from the bark and wood of this tree. John Robert McPherson, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Derived from the hardy trees of Southeast Asia, this aromatic resin embarked on an odyssey across the Indian Ocean, weaving its way through the intricate tapestry of medieval maritime trade. As we trace camphor’s journey, we encounter the indefatigable Geniza merchants of the 11th century, whose trading networks stretched from the Iberian Peninsula to the distant shores of the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

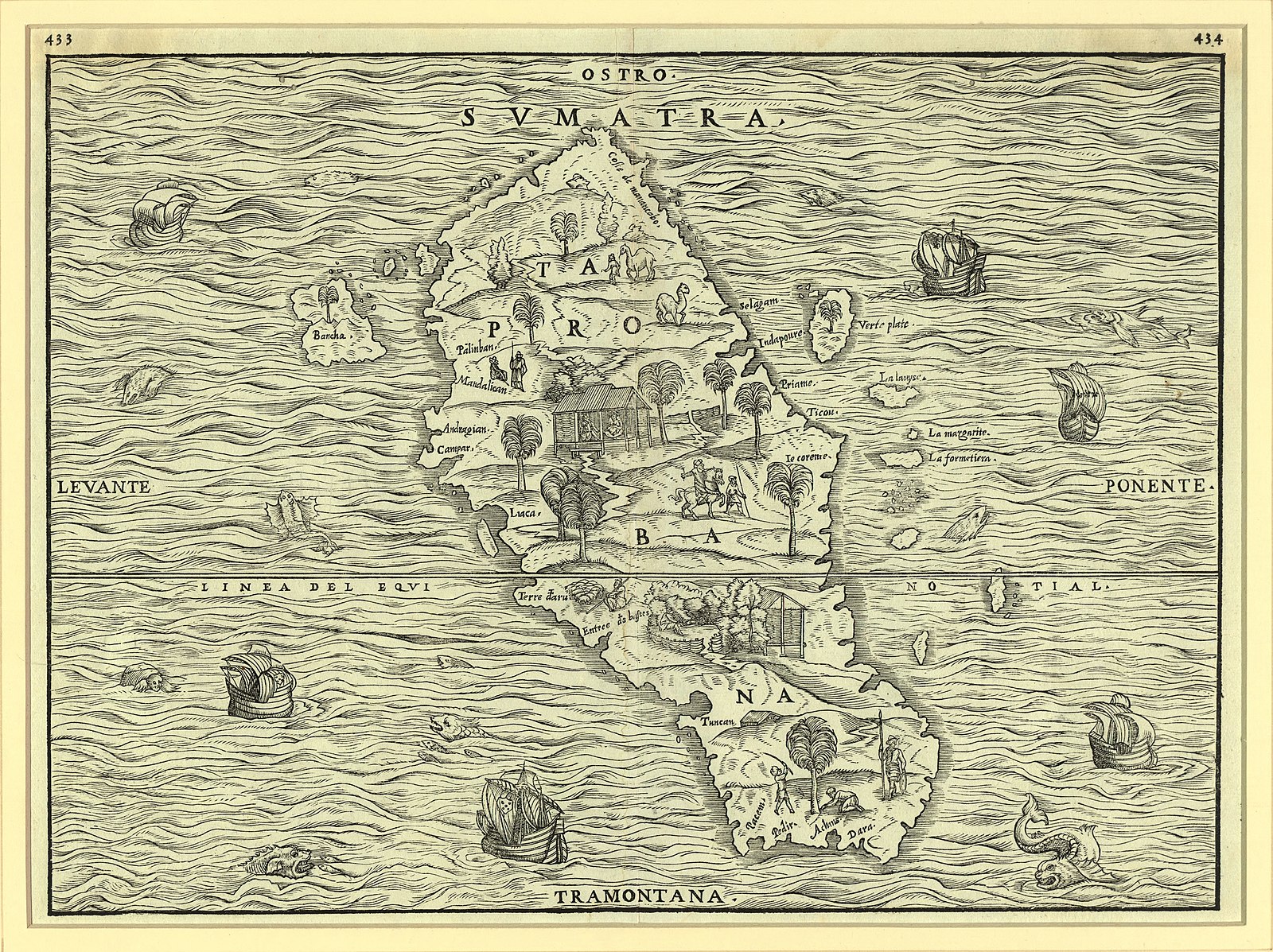

The sources of this coveted commodity were not found on the Indian subcontinent itself but rather in the distant lands of Southeast Asia, primarily the famed Fansur (modern-day Barus, Sumatra). Historical accounts converge on this consensus, underscoring the maritime trade networks that facilitated the transportation of Sumatran camphor to distant West Asian markets.

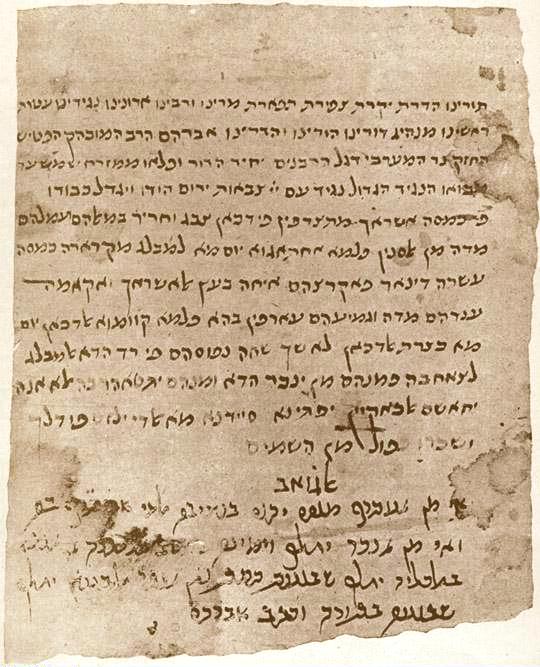

The Geniza merchants were primarily concentrated in the southern Mediterranean (Egypt), a strategic shift occurred as political instability and technological advances (primarily in shipbuilding) lured these merchants eastward, where the promise of new markets beckoned. It is here, amidst the bustle of port cities like Aden, that the true significance of camphor emerges. The enigmatic disappearance of a Jewish trader named Abu ‘l-Faraj Nissim, who sent a cargo of camphor from India to Aden after spending over more than a decade away from his family who were in Egypt. He appointed an agent to sell his cargo of camphor and give the proceeds of the sale to his family which would be a handsome amount and would easily sustain them for a long time was unfortunately lost to the complexities of not just the Indian Ocean trade but to also the behaviours of certain merchants acting in their own benefit, this underscores the risks and rewards of dealing in this precious commodity.

Figure 4: A Geniza Letter. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons

But camphor was more than just a luxury for the wealthy few. Its role in Islamic funerary rituals traced back to the instructions of the Prophet Muhammad himself, hints at a wider demand that transcended social strata. The Prophet’s guidance to wash the deceased with water infused with camphor’s fragrance became an integral part of Islamic burial rites, observed by both Sunni and Shia traditions.

In the Sunni tradition, particularly the Shafeʿite school, the triple washing and perfuming of the corpse with camphor and lotus leaves was recommended. For the Imami Shia, the practice of ḥanūṭ or taḥnīṭ (to prepare a corpse for burial with embalming substances) made the use of camphor obligatory, involving the rubbing of pulverized, fresh camphor on specific parts of the deceased’s body.

Beyond its spiritual significance, camphor found its way into the realm of medicine and fragrance production. Islamic physicians integrated it into Galenic medicine, recognizing its benefits in treating “hot” ailments while cautioning against its potential to suppress sexual desire if consumed excessively. The 9th-century treatise on perfume manufacturing, Kitab al Kimiya al-Itr, highlighted the utilization of camphor in creating aromatic blends.

Camphor appears to have been absent from the awareness of Greek and Roman antiquity. However, in the Near East, its utilisation as a spice and perfume is noted to have been established by Sasanid times at the latest. Upon the Arab conquest of Ctesiphon in 16/637, abundant reserves of camphor were discovered, although initially mistaken for salt by the conquerors. Ancient Arabia was acquainted with camphor, as indicated by Qurʾān 76:5, which references the refreshing of devout Muslims in paradise with a drink infused with the flavour of camphor.

As the centuries progressed, the once exorbitant prices of camphor began to decline, suggesting a transition from exclusive indulgence to a more accessible, if still prized, commodity. The evolving fortunes of camphor, as chronicled in the Geniza letters, paint a picture of a trading landscape in flux.

From the lofty heights of a luxury item commanding prices in the hundreds of dinars in the late 11th century, camphor’s value gradually decreased, with records indicating its sale at 80 dinars (One dinar is approximately 4 grams of gold) per mann (approximately 30-40kilos) in the 1180s and a mere eight and a half dinars by 1199. This trend suggests that camphor may have transitioned from a luxury item to a semi-luxury good, perhaps even edging towards the realm of bulk commodities as supply increased and new traders ventured into the Indian Ocean. Jessica Golberg argues that in the late 12th century the Geniza merchants who initially did not invest in ships and transport, started investing in them and this also increased the volume of traders in the Indian Ocean which inadvertently increased the volume of camphor being exported to Egypt.

Figure 5: Dinar (gold coin) from 11th century Egypt. Creative Commons License by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

As camphor’s odyssey unfolded, it traversed an intricate web of trade routes, passing through the hands of merchants in South India before making its way to the bustling port of Aden. From there, it would embark on the final leg of its journey, sailing across the Red Sea to the heart of the Fatimid empire in Cairo.

Yet, amidst this shifting landscape, one question lingers: did the common peasant truly have access to this aromatic wonder, so integral to the rituals surrounding death and the afterlife? The absence of fatwas addressing the availability of camphor suggests a lingering uncertainty, a veil of mystery shrouding the extent of its reach.

Perhaps the answer lies in the nuances of supply and demand, where even as camphor’s prices declined, its spiritual and medicinal significance may have kept it out of reach for the poorest segments of society. Or perhaps, as trade networks expanded and new sources emerged, camphor gradually transitioned from a luxury to a commodity within the grasp of a broader populace.

As we ponder these questions, the tale of camphor invites us to re-examine the narratives that have shaped our understanding of medieval trade. It prompts us to challenge assumptions, to look beyond the dazzling allure of luxury goods and consider the oft-overlooked bulk commodities that may have been the true lifeblood of maritime exchange.

The historiographical debate initiated by scholars like Wickham and Jessica Goldberg, who highlighted the extensive trading networks of Geniza merchants, has opened new avenues for exploring the complex dynamics of medieval trade. Through their lenses, we catch glimpses of a world where the boundaries between luxury and necessity were constantly being redrawn, and the ebb and flow of trade could elevate the ordinary to extraordinary heights.

In the end, the aromatic journey of camphor through the medieval Indian Ocean trade is more than just a fragrant footnote; it is a window into an era of shifting fortunes, where the value of goods was shaped by the intricate interplay of demand, supply, and societal perceptions. Its tale serves as a reminder that the true riches of history often lie not in the glittering rarities but in the seemingly mundane commodities that sustained cultures and connected distant lands.

As scholars continue to explore the intricacies of medieval trade, this aromatic odyssey invites us to embrace the complexities and nuances that lie beneath the surface, to challenge long-held narratives, and to embrace the rich tapestry of stories that have woven the fabric of our shared human experience.

Further Reading:

Abraham, Meera. Two Medieval Merchant Guilds of South India. Manohar Publications, 1988.

Baladhuri, Ahmad b. Yahya al. History of the Arab Invasions: The Conquest of the Lands. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.

Chakravarthi, Ranabir . Aromas across the Sea. Camphor to India, beyond India. Edited by Osmund Bopearachchi and Suchandra Ghosh. Primus Books , 2019.

Eliyahu Ashtor. Levant Trade in the Middle Ages. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Rex Smith. A Traveller in Thirteenth-Century Arabia / Ibn Al-Mujawir’s Tarikh Al-Mustabsir. Routledge, 2017.

Goitein, S D. A Mediterranean Society : The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Vol. Volume I: Economic Foundations. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Goitein, S D, and Mordechai Akiva Friedman. India Traders of the Middle Ages : Documents from the Cairo Geniza. India Book, Part One. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

Goldberg, Jessica L. Trade and Institutions in the Medieval Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Robert Sabatino Lopez. The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages : 950-1350. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pess, 2005.

Roxani Eleni Margariti. Aden and the Indian Ocean Trade. UNC Press Books, 2012.

Rustow, Marina. The Lost Archive : Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Wickham, Chris. The Donkey and the Boat. Oxford University Press, 2023.

An interesting and educative article highlighting the interlinking of traditional believes, trade and transport…an unexpected historical view of valuable camphor.