27 July 2017 marked the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, recognised as decriminalising male homosexual acts that take place in private. Coinciding with this, Tate Britain is hosting Queer British Art 1861-1967. With the death penalty for acts of sodomy abolished in 1861, Queer British Art spans the following century, displaying a variety of artistic expressions with a queer sensibility, including work by Simeon Solomon, Hannah Gluckstein, Henry Scott Tuke, Dora Carrington, David Hockney and Francis Bacon. By combining artefacts alongside artwork, the exhibition provides a mixture of social and art history. Noel Coward’s dressing gown, and the library books doctored and defaced by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell (a ‘crime’ for which they were jailed, following an investigation that involved undercover librarians!), hang alongside portraits of Quentin Crisp, Vita Sackville-West, Radcliffe Hall and Virginia Woolf. Lesser known faces, such as Berto Pasuka, the co-founder of the first black British ballet troupe Les Ballets Negres, also make an appearance.

William Strang, Lady with a Red Hat (Vita Sackville-West), oil on canvas, 1918. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

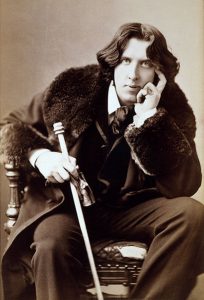

Perhaps the most (in)famous figure present is Oscar Wilde. While his central position in the ‘Public Indecency’ room is historically and thematically appropriate, the inclusion of a portrait painted over a decade before his trials – a full length image of a confident Wilde, captured on the cusp of fame – also suggests that his artistic output is as much part of his enduring reputation as his fall from grace. The exhibition includes the Marquess of Queensbury’s notorious calling card, left for Wilde and accusing him of ‘posing as somdomite [sic]’, which prompted the disastrous 1895 libel case against his lover’s father. Nearby is the cell door behind which Wilde was incarcerated when his ill-judged libel action spectacularly rebounded and he was instead found guilty of acts of gross indecency with young male prostitutes, receiving two years imprisonment with hard labour.

Napoleon Sarony, Photographic portrait of Oscar Wilde, c. 1882. Library of Congress. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

The specific clause that Wilde was tried under – the Labouchere amendment – outlawed all sexual contact between men in both public and private and was part of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act (CLAA). This Act raised the age of consent for heterosexual sex from 13 to 16 and increased anti-prostitution measures. It was ushered in during an era of social purity campaigning, with reformers determined to curb immorality and protect the vulnerable. Crusading explicitly against sexual debauchery, social purists did not differentiate between homosexual acts and prostitution, seeing both as aspects of an unrestrained and corrupting male lust. Contributing to this atmosphere of social purity and control, a sensational piece of journalism – W.T. Stead’s 1885 exposé of child sex trafficking, ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’ – added further fuel to the moral panic that led to the passing of the CLAA. Contained within the Act was MP and journalist Henry Labouchere’s amendment. His motivation for this is unclear, but as the idea of a specific homosexual type barely existed, it appears that he was aiming widely at general male sexual depravity – for many the foundation of vice – rather than those who may have specifically identified as homosexual.

This suggests that Wilde’s reputation as a gay martyr – persecuted for his unrepentant homosexuality – is somewhat misleading. At the time of his trials what we now recognise as a specific homosexual identity was only just emerging. The labels ‘invert’ or ‘homosexual’ were not widely understood or used, and their absence in both the court records and newspaper reports of Wilde’s trials suggests that he was not identified as such. German writer Karl Ulrichs was the first to develop a scientific concept of homosexuality in an article published in 1864. The term ‘homosexual’ was first seen in Britain in 1892, in a translation of Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis – a study of deviant sexual practices. Wilde never admitted to being a homosexual, and in retrospect saw his own sexual conduct as that of someone dealing with mental ill health. The self-assurance captured in his exhibition portrait is certainly not that of an unapologetic gay rights pioneer. Opposite Wilde’s image, the exhibition places portraits of some of Wilde’s contemporaries: English writers Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds, along with sexologist Havelock Ellis. They were the first in Britain to begin formulating a gay rights agenda. Their inclusion here acknowledges the important role that dialogue between science and the arts played in developing and promoting the idea that homosexuality was inherent. Together, these three men advocated for homosexuality to be seen as a congenital condition, one that shouldn’t be subject to legal penalties. By the end of the nineteenth century their texts began slowly introducing these concepts into the English lexicon.

Roger Fry, Portrait of Edward Carpenter, 1894. Oil on canvas. NPG 2447 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

The emergence of the modern male homosexual in the late nineteenth century should be differentiated from homosexual behaviour. Men have always had sexual interactions with each other, with the idea that some of these men constituted a differing sexual minority emerging in the 1700s. The association of these acts with a specific identity is a more recent construct – one that had only just begun to crystallise around the time of Wilde’s trials. Public sites where men could have sexual encounters with one another – parks, public toilets or even specific streets – could be easily accessed by those who chose to, and the often casual and opportunistic nature of these liaisons allowed them to remain separate from a person’s identity. Homosexual acts do not necessarily confer a homosexual identity, and to assume Wilde’s various homosexual encounters means that he identified – or was identified – as such would be to retrospectively impose an inflexible, late twentieth-century concept of homosexuality onto what was then a more fluid and ambiguous notion of sexuality.

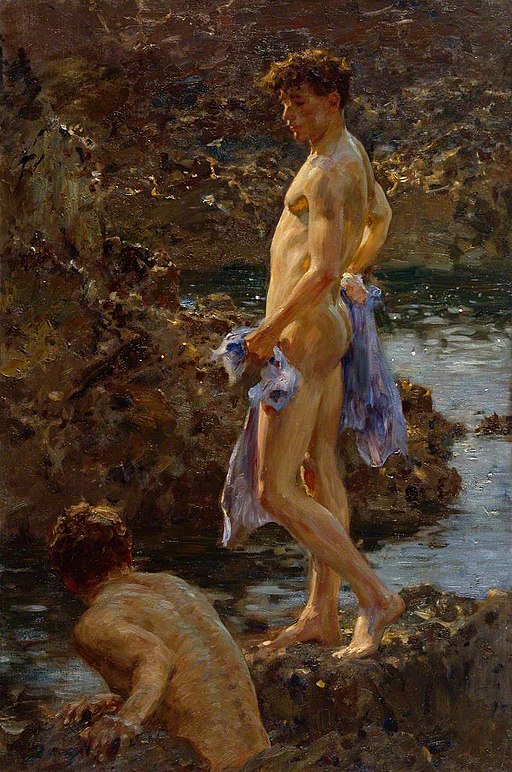

Henry Scott Tuke, A Bathing Group, oil on canvas, 1914. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

As the curators of Queer British Art make clear, LGBT+ labels were not recognised for most of the period their exhibition covers, by individuals or wider society, artists or their audiences. The term ‘queer’ in its current usage can be seen as an umbrella term, used to encompass all non-heterosexual, non-cisgender identities. The curators’ use of this broader term avoids this imposition of retrospective labelling, and by acknowledging the fluidity that exists around sexual identity, it provides a more accurate representation of the reality. With a 2015 YouGov survey suggesting that almost half of 18-24 year olds do not define themselves as exclusively heterosexual, it is perhaps ironic that today’s apparently more relaxed and fluid forms of sexual identity have more in common with the Victorian era – despite its reputation for prudish sexual repression – than is first apparent.