When it comes to imagining or describing historic and modern day practices of the occult, it is hard not to conjure up an image or experience that has been seen or heard via some form of technology. As part of the ‘millennial’ generation, it is even harder to consider the occult without technology, be it through the medium of smart phone photography, film or TV. The relationship between the two, however (and perhaps, thankfully), is not rooted in dodgy film franchises or programmes like Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Charmed. The relationship is more entrenched, and took a particularly intriguing form in the second half of the nineteenth century in the shape of ‘spirit photography’.

Technology, much like that of today, was held in great esteem but was also not without its sceptics. The relationship between technology and the occult during the second half of the nineteenth century was complex to say the least. Photography, depending on the use of it, had the ability to undermine or legitimise faith in the occult. In what can be taken as a prelude to our current obsession with capturing everything on camera, people in this period also used photographs to capture and preserve images of themselves and those around them. They also used the camera to photograph those who were no longer ‘actively’ present, for example, the subjects of post-mortem photography. Photography was also being used in the field of natural science, capturing and legitimising what had previously been invisible to the human eye. The camera reinforced the possibility of discovering and seeing things that were hidden from human visibility, an idea that was easily transferable to spirits and the séance.

Getting into the spirit of things: The rise of, and problems with, spirit photography

Spiritualism was an occult practice that arrived in Britain from the USA in the 1850s. In spiritualism the human body acted as a host for communication with spirits. Those who were predisposed to mediumship (predominantly young women) were able to channel multiple beings, which they did in both domestic and public settings, often for paying audiences. Spirit photography was a by-product of spiritualism, spread from the 1860s by the Bostonian William Mumler. Like spiritualism, it travelled to Britain and soon became popular owing to spiritualist figures such as Frederick Hudson. Spirit photography, as a practice, did what it said on the tin. Mediums and spirit photographers took photographs during séances, producing photographic ‘evidence’ of tables being raised above the ground and spirits surrounding participants. The legitimacy of spirit photography was often (and perhaps, justifiably) contested, leading to accusations of fraud and scientific investigations into photographers and their products. Mumler, for example, was arrested and charged with fraud in 1869 but later acquitted.

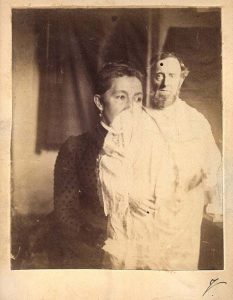

William Eglinton, Mary Burchett with Spirit of her School-Master, 1886. Image source: American Museum of Photography.

In this respect, whilst the faith of contemporaries in the capability of the camera encouraged and justified a belief in the occult, sceptics did not necessarily accept spirit photography as genuine even when they could not prove otherwise. Investigations into spirit photography included testing the components of the camera and the printed image itself. Photographs were susceptible to manipulation and contemporaries of the period were well aware of this, including Charles W. Hull who identified several potential methods of achieving this. However, those who investigated spiritualist practices did not necessarily shy away from using spirit photography themselves. William Crookes, for example, used cameras in an attempt to photograph a spirit named Katie King who was being channelled by a young medium named Florence Cook. Crookes, in an interesting turn of events, also became a president of the Society for Psychical Research. The SPR was founded in 1882 and many members from the late nineteenth century onwards concerned themselves with investigating the practice of spirit photography. During the twentieth century SPR members such as Harry Price continued to investigate and publish their findings on photographers like Frederick Hudson, keeping the debate about spirit photography alive in society even when the photographer (and their subject) wasn’t.

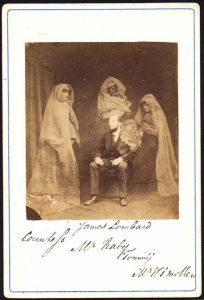

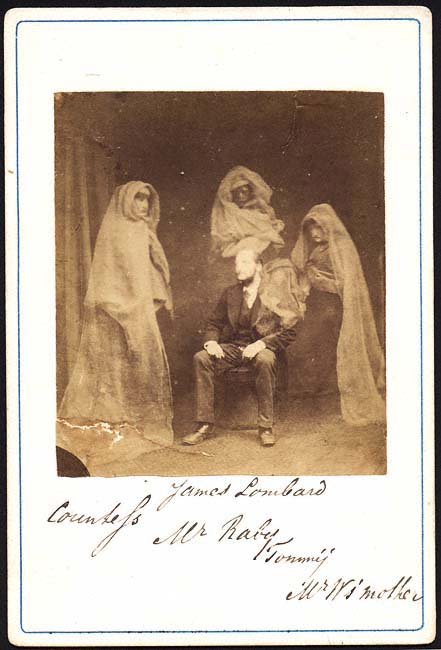

Frederick A. Hudson, Mr Ruby with the Spirits ‘Countess’, ‘James Lombard’, ‘Tommy’, and the Spirit of Mr Wootton’s Mother, c. 1875. Image source: American Museum of Photography.

Ultimately, the camera helped many spiritualists to achieve their goal of making the previously invisible visible, to large (and often paying) audiences. Despite this, they were unable to prevent the scepticism towards their practices that was in part brought about, or at least heightened by, spirit photography. The products of spirit photography were treated with additional suspicion because contemporaries knew that technology was vulnerable to misuse. The camera revealed things to Victorian society that were previously invisible to the human eye. However, much like today, the potential distortion of images drew the attention of sceptics who sought to rationalise the images and expose them for what they thought they really were.

hi, I am searching for the documentery about the occult live of sir Dr. William Crookes. It is all about experimemts, moving objects caused by spirits.