Johan Huizinga’s ‘The Autumn of the Middle Ages’ is an ambitious exploration of—and reflection on—the expansive period of time between Classical Antiquity and the early modern period. Huizinga uses a variety of different intellectual frameworks through which to extrapolate his ideas about the late Middle Ages, but it is his views on art during this period which are of particular interest for this author. For Huizinga, art performed specific functions in the life of French-Burgundian society of the late medieval period, functions that reflected the changing religio-political landscape on the cusp of the Early Modern era. Huizinga understood that art made in the Middle Ages was primarily about the object serving a crucial purpose, usually religious in nature, and that desiring a work of art was entirely linked to its intended purpose—how this object would best serve life. He was not wrong in his assertion. Europeans were not, at this point, living during the ‘cult’ of the superstar artists: think Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael. But rather, art was at the mercy of Religion and was a medium for devotion. He notes that a work of art usually always had a specific end, a specific purpose connected with daily life—and for the medieval person, daily life and religion were intertwined beyond separation.

What Huizinga observed was that as time moves forward and the Middle Ages ‘wane’ the function of art also shifts. He writes: ‘Late medieval art reflects the spirit of the late Middle Ages faithfully, a spirit that had run its course.’[1] Huizinga sees French-Burgundian culture as one where ‘beauty has been replaced by splendour.’[2] This is a fascinating idea that deserves to be unpacked further as he goes on to write that: ‘Art was used to intensify the splendour of life itself.’[3] While this is true, as seen in myriad example of art produced during the late medieval period, what is perhaps more interesting is the idea that art began to serve multiple functions, not purely religious ones. This notion can be seen in much of the creative output of the early modern period—not only in the Low Countries and French-Burgundian culture but also in Italy and Spain. But it’s also critical to keep in mind that the varied functions of art were—to a greater or lesser degree—the result of social, political, economic, and religious factors.

As an art historian who specialises in Italian art of the late Middle Ages, I can speak directly, to this conception of art’s function, within a monastic setting. My work on large-scale choir books—which contained the music and text necessary for performing the Mass—has demonstrated that certain monastic orders used the books as vehicles for self-expression as well as religious tools. More than serving this critical function, as vehicles for liturgical materials, these books were sumptuous objects, lavishly-decorated with full-page images, comprised of colourful (and expensive!) pigments, burnished gold, and sometimes precious and semi-precious stones. I reconstructed a series of now-dismembered Venetian choir books made in ca. 1420s–1440s for the Camaldolese house of San Mattia di Murano, and attributed to the so-called ‘Master of the Murano Gradual,’ and what I found surprised me: the monks used the lavish codices to tell themselves about themselves, vis-à-vis the iconography in the illuminations. So, while still serving a crucial liturgical function (which really was their original intention), these books also functioned as mirrors for the monks to perceive and understand their place in the wider Benedictine community and the larger Christian cosmos.

What is also important to remember is that these books were conceived, not as ‘art’ but as necessary spiritual tools. The driving force behind the lavishness of the manuscripts was a deeply-rooted desire for the monks to understand themselves in relationship with the Divine—this is a variation of what Huizinga was expressing when he wrote that art was intended to enhance the splendour of life. Since God was the raison d’être for these monks, to facilitate an understanding of one’s life purpose within a larger Christological context would have been a way to enhance the ‘splendour of life.’

For Huizinga, however, certain artists that are considered iconic in the art historical canon are merely harbingers of the Middle Ages and contribute very little to the advancement of visual art. Jan van Eyck, in particular, represents almost a failing of the potential that Huizinga sees in the transition from Medieval to early modern visual culture. He acknowledges that van Eyck’s style and technique, particularly in the rendering of sacred objects, had advanced pictorial arts and in a historical sense was a beginning but in his opinion was, in fact, a conclusion. And, perhaps more unkindly, that van Eyck—and his contemporaries—were not announcements of the Renaissance’s arrival but rather the true unfolding of the medieval spirit.

While one can see that Huizinga was probably drawing this conclusion based on a purely visual ideology—he would look at the way in which van Eyck rendered figures, landscapes, objects and suggest a less refined end-product—he is missing an important point, which is that van Eyck was creating images unlike anything seen prior. Huizinga’s critique is based on Formalist ideas, which simply put is the methodology of comparing and analysing art based on its form and style. And while it is a perfectly legitimate theoretical framework, it does not take into account the other aims and ideologies at play in art that was as complex as van Eyck’s corpus. Van Eyck was less interested in formal interplay between his figures and more concerned with the deep emotional and psychological effect that his paintings seemed to achieve.

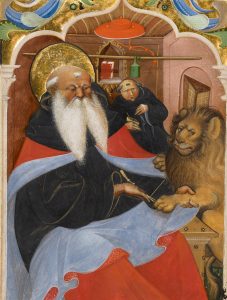

Historiated initial ? with St. Jerome and the Lion, Master of the Murano Gradual,

Venice, c. 1420s – 1440s. Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, ms. 106.

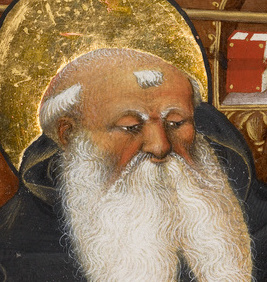

I have seen the same interest in rendering human psychology in the Murano Master’s illuminations for the aforementioned choir books. The Murano Master’s desire—and ability—to convey complex inner emotions was so refined and well executed that it has become one of the salient features of his corpus. In this example of a fragment, now in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles,[4] we see St. Jerome sitting in his study with the Lion. He very gently removes a thorn from the Lion’s paw, while a frightened monk cowers in the background. In this cropped close-up, we can see the minute details on the face of St. Jerome that the Murano Master has included: the furrowed brow created by folds in the skin, the delicate, wispy eyelashes and brows; the deep grooves in Jerome’s cheeks, and the heavy-lidded eyes so focused on the task of removing the thorn. All of these features, rendered with such careful attention, convey a pensive inner psychological state.

Saint Jerome Extracting a Thorn from a Lion’s Paw; Master of the Murano Gradual (Italian, active about 1430 – 1460); Northern, Italy; second quarter of 15th century; Tempera and gold leaf on parchment; Leaf: 21 x 16.5 cm (8 1/4 x 6 1/2 in.); Ms. 106, recto

This is not to say that Huizinga was wrong is his assessment of how art in life shifted between the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, but the medieval period has always had to shake this unfortunate reputation that the art produced during this long history was ‘primitive.’ The term ‘Dark Ages’ is a highly inaccurate label given to the Middle Ages for so long in scholarship that we are constantly repeating that there is no place for this description in discussing this period. Moreover, the shift in art from the late Middle Ages to the Early Modern period was both gradual and swift, as certain technical advancements, such as the use of linear perspective, were developed and implemented quickly. Artists, all over Europe, were keen to experiment with visual cultural, but there were certain techniques and motifs that stood the test of time and remained integral parts of these various visual cultures for much of the Renaissance. Ultimately what Huizinga was trying to achieve is a sense of linear, forward moving historical narrative about the development of art and its role in life during the ‘waning’ of the Middle Ages. While not all of his observations are accurate, his writing serves as a significant lens through which deeper conversations about art can—and should—occur.

It is also worth mentioning that the Museum of Fine Arts (MSK) Ghent is running an extraordinary exhibition of Jan van Eyck’s work, entitled: Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution. More than 50% of all van Eyck’s works have been brought together for this show. It runs 1 February – 30 April 2020.

It is also worth mentioning that the Museum of Fine Arts (MSK) Ghent is running an extraordinary exhibition of Jan van Eyck’s work, entitled: Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution. More than 50% of all van Eyck’s works have been brought together for this show. It runs 1 February – 30 April 2020.

[1]Johan Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages, R. J. Payton and U. Mammitzche, trans. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996), p. 300.

[2] Huizinga, The Autumn, p. 300.

[3] Huizinga, The Autumn, p. 296.

[4] Historiated initial ? with St. Jerome and the Lion, Master of the Murano Gradual, Venice, c. 1420s – 1440s. Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, ms. 106.