As the exhibition, ‘The Vexed Question: 500 years of women in medicine’ drew to an end, it was incredible, though not surprising, to see the compelling feedback and response from visitors as well as members who wanted to keep the history of women at the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) permanently displayed. I too was a little sad to see the inspirational, all female wall hangings being taken down. Having been entrusted with creating a permanent display for the anteroom chamber, I decided to be the genie to answer their wishes! I was going to create a permanent display on the history and contributions of the hidden women in the history of the RCP. But this proved to be a lot more challenging than I thought it would be.

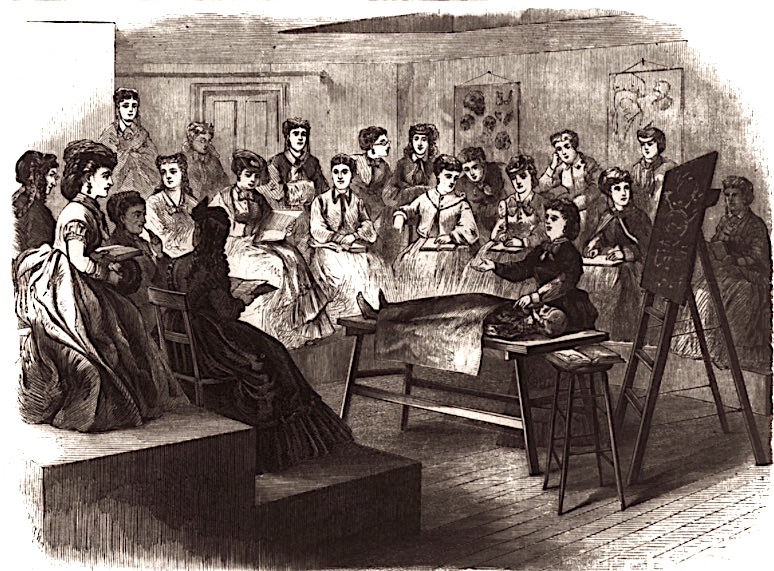

All-female portraits wall display; Royal College of Physicians, Photograph authors own from ‘500 years of women in medicine’ exhibition.

Before I began researching, I assumed that the hidden nature of the history of medical women was because of their exclusion from the formal sphere of medicine. This of course is partly true. When Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836–1917) was denied the right to apply for a licence from the R oyal College of Physicians, the College denied her request on the grounds that the 1518 founding charter only explicitly gave it the power ‘to permit men to practice medicine’. I immediately assumed that the use of the term ‘men’ was not intended to be used to exclude women from practicing medicine. Rather it was more of a synonym for ‘person’. But as I researched more into the history of the College, I learnt that the RCP did not just exclude women, but took an active approach in discriminating women practitioners. In a section of a 1693 translation of the RCP’s statutes, it explicitly ‘forbid all persons practising physick [from cooperating with] those idiots and silly women who carry the pis[s]pots of sick persons about’. So, women only rarely appear in College records. When they did so, it was usually for disciplinary action or punishment for the unlawful practice of medicine.

Objection I say! Unfortunately, our insight into these hidden women in the history of the RCP are through court papers or disciplinary record and there isn’t that much which can be done. Take for instance Elisabeth Pratt. Unheard of, a ghost in the history of medicine if it wasn’t for her signature at the bottom of a formal bond in the College collection. The only writing legacy and record of her medical work is her admitting treating Mary Morecock for a sore throat with ‘crude mercury’ for 40 shillings. Morecock later died, and Pratt was fined £15 by the College censors and sent to Newgate Prison. The nature of the recorded history of women medical practitioners thus only gives us a glimpse into their work. It really poses historians with a challenge of trying to grapple and understand the extent of women’s work in the medical field. Can we extrapolate, using the nature of sources that exist, the number of women working in medicine at the time?

James Barry was an army surgeon. Upon his death, it was discovered he was a woman. Photograph sourced from Scanty Particulars by Rachel Holmes; original photographer unknown

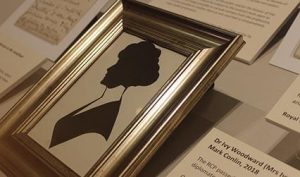

An 1895 petition, organised by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, demanded women be permitted to sit the RCP exams. That petition was unsuccessful, but a further campaign launched in 1907 finally compelled the RCP to admit women as members in 1909. The very same year, Ivy Woodward (1877-1957) became the first women member of the RCP. Great I thought! Surely now that women have formally entered the medical sphere then more material and sources will be available. I’ll be able to get a greater insight into women in medicine. Though in theory the College changed its clauses, it did not change its stance towards women until the middle of the twentieth century. Despite Woodward’s great importance in the College’s history, it was painstakingly difficult to find information on Woodward. It took trawling through census records and medical registers to flesh out her biography, including her posts at the Royal Free Hospital, the New Hospital for Women, Warneford Hospital, Belgrave Hospital for Children, and as Medical Inspector for Infant and School services. Yet despite the great efforts to find images of Woodward, she is a name without a face. The RCP does not hold any images of Woodward.

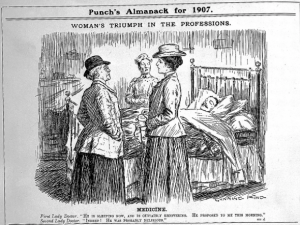

Image produced by Gunning King, Punch Magazine,1907, Sourced from Welcome Collection.

Now that it has become clear that both women’s recognition in the medical sphere coupled with change in attitudes towards women plays a significant role in accessing this hidden part of history, I assumed that finding the first fellow who was a woman of colour would be easier. But I am sure you have already guessed, it was far from easy. I jumped straight into searching secondary materials on the history of the RCP and the online catalogues. But alas my efforts were in vain! It could very much be that no one has conducted such research before and therefore I had to start my research from the basics.

Zahira Abdin was the first Egyptian woman to become a member and later a fellow. ‘The mother of Egyptian doctors’, Abdin identified the Streptococcal strain as a cause of rheumatic heart disease. She campaigned relentlessly against rheumatic heart disease; at the time, it was one of the leading causes of mortality among children in Egypt. Less than two decades later, the incidence of fatalities from rheumatic heart disease had dropped from 47 per cent to less than three per cent. I took to the Monk Rolls, a biographical resource which contain the names of every fellow of the RCP. It took scrolling through every single name of eight volumes of the Monk Rolls to find this hidden gem of information. The first female member was in 1909 and so I began searching from this point onward. What became apparent is that there are so many hidden women physicians who made outstanding contributions to the field of medicine.

Silhouette portrait by Mark Colin representing Ivy Woodward. Photograph authors own from RCP ‘500 years of women in medicine’ exhibition.

After scrolling through six volumes, I finally found the first woman of colour fellow- Sujata Chadhuri. I took to RCP storage room to see if I could find any more information, but like Ivy Woodward, Elisabeth Pratt, Alice Culpeper, Chaudhuri and Abdin were just names without faces. It was only because of an email sent by Abdin’s daughter, was I able to learn in more detail about her work. It then became apparent that the way we collect and gather information on the women members of the RCP plays an important role in how they are remembered. In fact, as I sit here writing this blog, the museum team are working through boxes of membership forms to try and pair up photos with the correct application forms.

As I assembled my display with the sources I had found on Woodward, Sujata and Abdin, I wanted to clearly relay the message that our understanding of the history of women in medicine is still incomplete. 500 years of women in medicine does not have to mean 500 years of forgotten history though. There are still so many gems waiting to be discovered. We are still in the process of unmasking all these hidden figures. My display was only a drop in an ocean of information on the history of women in medicine. By changing the ways in which we store and record information perhaps the history of women in medicine will become much more accessible. In 2007 a study showed that women make up 57% of both applicants and acceptances for medical schools. Women have made significant progress in the field of medicine, coming a very long way from the days women would vigorously fight to just be recognised as medical practitioner. But this long history is hidden history, and RCP has 120 years of hidden history yet to uncover.

As I assembled my display with the sources I had found on Woodward, Sujata and Abdin, I wanted to clearly relay the message that our understanding of the history of women in medicine is still incomplete. 500 years of women in medicine does not have to mean 500 years of forgotten history though. There are still so many gems waiting to be discovered. We are still in the process of unmasking all these hidden figures. My display was only a drop in an ocean of information on the history of women in medicine. By changing the ways in which we store and record information perhaps the history of women in medicine will become much more accessible. In 2007 a study showed that women make up 57% of both applicants and acceptances for medical schools. Women have made significant progress in the field of medicine, coming a very long way from the days women would vigorously fight to just be recognised as medical practitioner. But this long history is hidden history, and RCP has 120 years of hidden history yet to uncover.

Further Reading

The Guardian: Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time review- an exquisite story of scandalous subterfuge.

Sinead Spearing, A History of Women in Medicine: Cunning Women, Physicians, Witches. Great Britain: Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2019.

Royal College of Physicians online archives: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/education-practice/library/historical-research-materials.

Royal college of Physicians Museum: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/events/under-skin-illustrating-human-body.