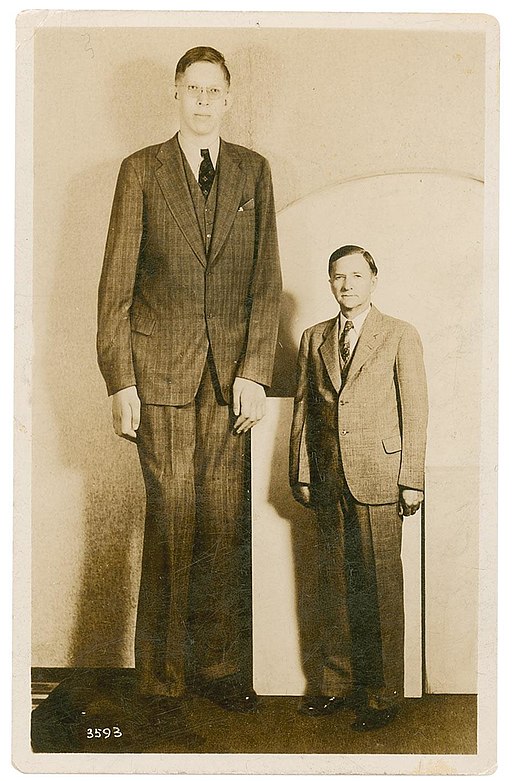

‘I do not love mankind.’ This is the opening line of Elizabeth McCracken’s 1997 novel, The Giant’s House. The fictional story set in 1950s New England focuses on James Sweatt, a young man who by the age of 20 has reached 8’7”. Written from the perspective of town librarian Peggy Cort, the novel examines James and his life of fame, with his goal of becoming a lawyer dismissed early in his life. Although the story of James Sweatt is fictional, his life closely resembles that of Robert Wadlow, the tallest person in history. Robert was born on February 22, 1918, in Alton, Illinois. Although he was of typical size when born, he had reached 6’2” by the time he was eight. Both McCracken’s novel and the story of Robert Wadlow show how an ordinary boy’s life may be defined by his extraordinary body, but also makes us question why we are so enduringly fascinated by those who we deem different.

The fictional James Sweatt invests his time in books, which is how we meet our ‘eyes’ of the story, Peggy Cort. It is through their early interactions that the sadness that clouds James’s tale becomes apparent. When James is 16 and standing at 7’6” he comes to the library looking for books on people like him. Searches under height and stature are unsuccessful. Peggy takes the task upon herself and it is under giants that she finds results. The tall people mentioned under these headings had worked for circuses, or as professional giants. The source Peggy finds most useful is a nineteenth-century book on medical curiosities. Under abnormalities, she finds ‘giants’ alongside ‘two-headed people and parasitic twins and dwarfs.’ The pages are marked and handed to James.

The extreme growth of both James and Robert was due to an over-active pituitary gland, which causes high levels of growth hormones. But this scientific explanation does not answer all of our questions. Are these men able to function normally in society? How are they treated? Where do they belong? It is these questions that we see James battle with. Again, James’s story closely reflects that of Robert Wadlow. At 18 Robert required three times the normal amount of cloth to dress him. His shoes, at size 37, had to be specially made at $100 a pair, a high price for the 1930s. By the time he was 20 he was having his shoes made and paid for by the International Shoe Company. Robert travelled across the country, greeted by huge crowds, made into an exhibition in return for having shoes that fit him.

In the novel James Sweatt’s life proceeds slightly differently. James has a dream of visiting New York, something promised to him by a shoe company, but which falls through when the state of his feet is revealed. Both our fictional and real-life ‘giant’ had little feeling in their feet due to their large size. James is unaware of the dire state his feet are in, which is deemed bad publicity for a shoe company promising comfort and fit. Instead he finds another route to New York: the circus. James at first declines this job as he wants to do something with dignity. It is hard to put ourselves in his shoes, but as an outsider you can see that both the shoe company and the circus are a form of exploitation, each commodifying his body to advance their sales.

Robert and James die of similar circumstances. Their unfeeling feet were their ultimate downfall. Robert died from an infected blister in 1940, during promotions for the International Shoe Company. He was 22. In the novel James dies from an infected sore on his ankle from his leg brace. He is 20. It is with his death that McCracken again reminds us of the sadness and anxiety that has marked James’s life. In his final moments he insists Peggy protect his body, to ensure it remains intact and at rest. It was from Peggy’s library searches that James had read about Charles Byrne, the ‘Irish Giant’ whose bones are still contentiously displayed at the Hunterian Museum. Byrne had been a spectacle all his life and did not want this to continue in death. The book Peggy gives James as a child comes to define his adult fears.

In telling the story of James Sweatt and Robert Wadlow there is one final sadness which must be understood. The fictitious Sweatt family react to his death by opening his living space up to the public, making it a tourist spot in their small New England town. Some see this as sweet, a way to preserve his memory. Others see it as disrespectful, one final means of making money from his hardship. The story of the real-life ‘giant’ is perhaps more heartbreaking. Upon Robert’s death in 1940 his family destroyed almost all of his belongings. They did this out of fear, and a deep amount of love and respect for their late son and brother. They knew that, given the opportunity, collectors would try to turn his personal items into ‘freak’ memorabilia. The current museum in Robert’s hometown says that it is with pride and dignity that they display the few items that remain.

It is easy to look at the fictional story of James Sweatt and the real-life story of Robert Wadlow and assume that these two men were accepted into their communities. Both had loving families and friends, both were largely able to live an ordinary life, especially in their youth. But their experiences of work show a different side to the story. Both men were treated as something to gawk at, a rarity to increase shoe or ticket sales. They were not allowed to be normal.

The stories of these ‘gentle giants’ are, one hopes, from a different time. With modern medicine an over-active pituitary gland can be compensated for. Nowadays the idea of the ‘freakshow’ is no longer acceptable; the majority of the old-style circuses have disappeared. As people we want to believe that we are accepting of all human variety. But truthfully, when faced with something seemingly out of the ordinary we don’t quite know how to handle it: we turn it into a spectacle. We have moved away from the circus and the sideshow, but perhaps with the rise of reality television we have simply found new modes of showcasing bodies and lives that do not sit within our ‘normal’.

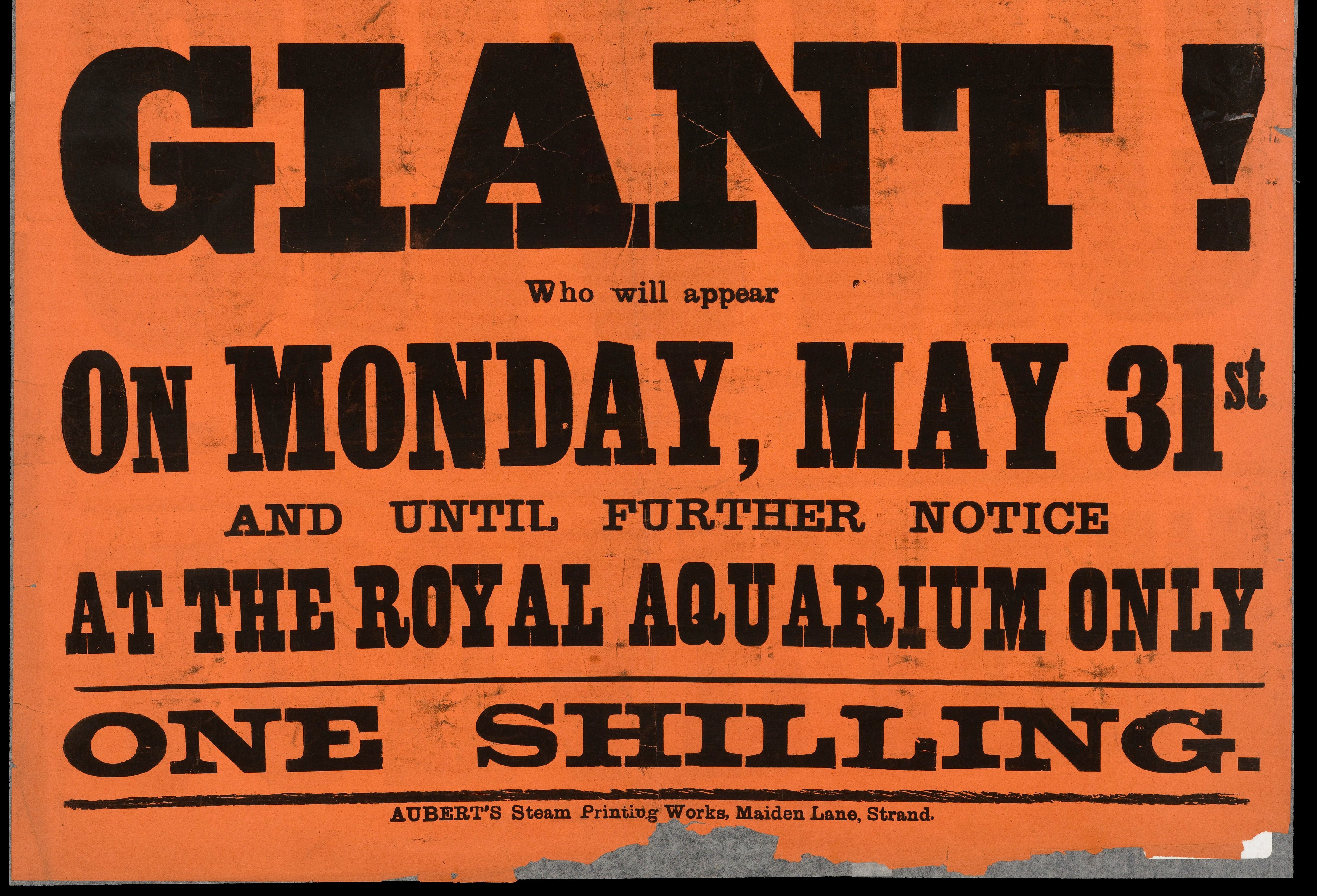

Header image: Detail from a poster advertising an appearance by the 19th-century ‘Chinese giant’, Zhan Shichai. Wellcome Collection.