At the end of April, thirteen postgraduate students and early-career academics from around Europe stepped outside their comfort zones to collaborate in a hackathon at Cambridge University Library. The event saw them create, from scratch, a set of functional web-based apps aimed at bringing the Library’s manuscript collections to a wider and more diverse audience online. The group, with expertise spanning medieval scholarship, digital humanities and web development, were first introduced to the manuscripts they would be working with on Monday afternoon. By Friday they were demoing their apps to an excited audience of academics, librarians and developers. Today, the apps they built are available online to explore and inspire.

A video tour of ‘The Lukes’ app exploring the Gospel of Luke. Click the image to go play. You can view an interactive prototype of the Lukes’ app online, here.

The teams selected their manuscripts from a set of writings known as ‘glosses’, which are medieval commentaries on a well-known text (typically the Bible) often supplemented, over later periods, by a range of authors. These ancient books were a good fit for the task: like the Web, the medieval gloss was a form that inspired technical adventurousness, and like our modern app developers its practitioners were concerned with the organisation and communication of complex information for an audience remote in time and space, and with making those complex texts more accessible. Of course, medieval glossators were writing for an elite group of literate men trained within the Church. Our participants, by contrast, chose from a set of four ‘personas’ crafted to represent a variety of modern users: from Leo the Traditional Scholar who knew his manicules from his marginalia, to Mariana the Leisure Learner, an untrained but inquisitive septuagenarian from the southern USA who discovered her love of the Middle Ages on Twitter. Selecting one of these personas as the target user helped our participants focus their design and development of their apps.

Most of the participants were alumni of the international Digital Editing of Medieval Manuscripts postgraduate training programme, and so had some familiarity with digital editing techniques, but the hackathon was something entirely new — to go from introduction to presentation in just three days, and publication a week later.

A video tour of ‘The Begees’ app exploring a gloss of Boetheus.

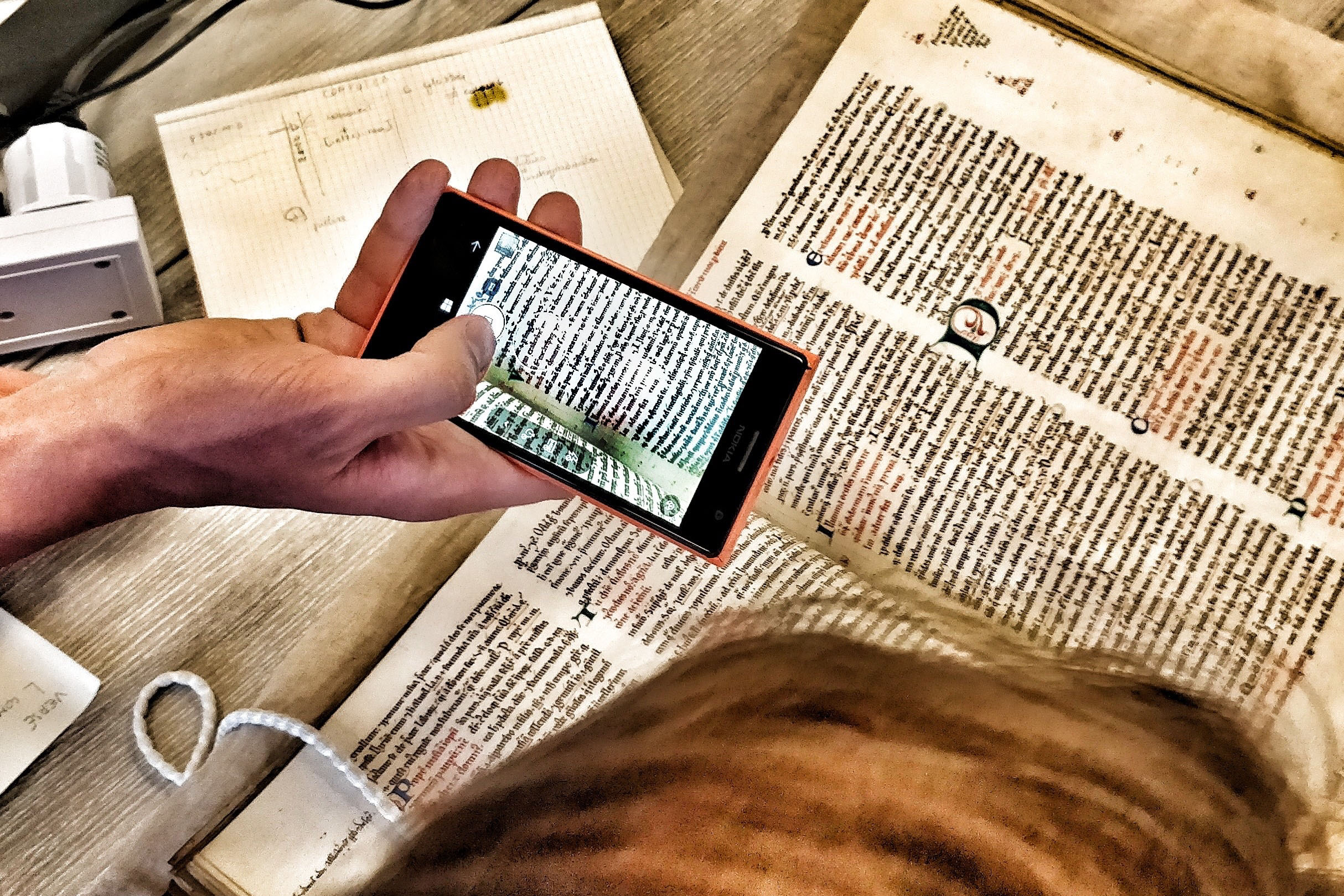

For the first couple of days we were keen to keep laptops shut and discussion flowing freely. Our teams sketched out their apps using pen and paper (appropriately distant from the manuscripts, of course) and presented them to the group on flipcharts. At this stage, lo-fi was better because it held the inner perfectionist at bay. As organizers, we were at first more focused on the ideas and the experience than on the products being developed. We wanted to give our participants an experience of collaborative production, and to kick-start their imaginations and ours to generate new ways of thinking about how to publish historical texts digitally, moving beyond images and transcriptions to take full advantage of the exciting new possibilities online. As the week unfurled, though, it became clear that our expectations — high from the start — were going to be exceeded. By Thursday, when the teams welcomed ‘beta testers’ to explore and comment upon the prototypes, the rough sketches of the beginning of the week had been replaced by intricate and detailed drafts; by the time they were presented on Friday, they were technicolour movies.

One of the most rewarding things about the week for me was the air of excitement, experimentation and friendship. It was hard to enter our digital factory in the basement of the library without picking up on the buzz. Collaboration isn’t always something we are always very good at in the Humanities, valorising as we do the model of the noble lonely scholar. Beyond relatively few centres of digital collaboration it is too often the same when we commission digital projects: code and content are split apart, and both are poorer for it. No one who saw our three teams at work would have questioned that these were truly co-productions.

A video tour of ‘The Lombards’ app which introduces readers to a gloss on the Psalms. Click to play. An interactive prototype of The Lombards’ app is available online, here.

Coding and writing are both creative acts, and they are both communicative acts. By expressing our ideas through language (more often languages, plural) we bring something new into the world and we can challenge, delight and hopefully help our audience to learn something new

Something of this last week brought back to me the excitement I had as a teenager when I first understood that not only could I pick apart the digital fibres of the websites I was beginning to discover, but — with no training and no instructions beyond what I could find online — I could weave them together again to create something entirely new. It wasn’t just me back then; those early days of the public internet and consumer broadband were idealistic ones. When I published my first website as a teenager I remember the excitement that this free-form, open-ended, anything-is-possible medium represented, and the promise that anyone could publish here free of interference and without having to pay. It is a truism today that this teenaged optimism was misplaced; Internet giants quickly tamed the beautiful chaos of the early web and brought the majority of us within their corporate walled gardens, which were well-tended but bland. But this week was a reminder for me that the Web remains the most extraordinarily accessible and powerful creative platform ever invented. And in the Humanities we have only begun to skate across the surface of what is possible.

Thanks my fellow organisers: Mary Chester-Kadwell (Cambridge Univeristy Digital Library), James Freeman (Cambridge University Library), Suzanne Paul (Cambridge University Library), and Eyal Poleg (QMUL History). Thanks also to our hosts at Cambridge University Library, and to the HSS Collaborative Fund at QMUL which provided funding for the event. Most of all thanks to all the participants.