Earlier this month I co-organised a workshop with David Morris, an archivist at the West Yorkshire Archive Service, as part of the University of Huddersfield’s ‘History in Action’ day. Our session, ‘Only a Picture? The Lives of Medical Photographs’, aimed to explore medical photography in the Victorian asylum through a mixture of brief talks and group discussions.

It was an opportune time to be talking about medical photography; my forthcoming book, Investigating the Body in the Victorian Asylum, is in production as I write this and relies heavily on medical photographs. During the work for that book, I’d thought more and more about how we use such visual resources, and the challenges that they pose. How ‘ethical’ was it to use pictures of patients, pictures that – when they were taken – didn’t require consent and would likely never have been envisaged as things to be included in a history book?

I went along to the workshop keen to hear other people’s thoughts on this. The workshop was envisaged as a two-way process: David and I would give an overview of photography in the 19th-century asylum and the challenges of working with such images from an archival perspective, and our participants would give us their ideas about a range of photographs from the archives of the West Riding Lunatic Asylum as well as a few other institutions.

The pictures we chose aimed to highlight five key themes:

- The practical aspects of photography in an asylum, such as who took photos, and where;

- Contemporary concern for preserving patient’s anonymity;

- The presence of asylum staff in photographs, who touched or held patients;

- The photograph as a means of charting treatment, as in the ‘before and after’ photograph;

- How such photographs might be re-used and re-purposed, and the ethics of that re-use.

A woman suffering from rupia at the Bristol Infirmary. Wellcome Images/Wellcome Library.

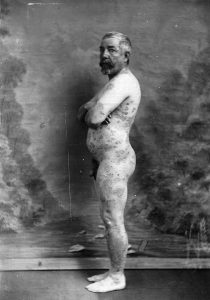

In discussing the photos in small groups, it was clear that the photographs could be read in various ways. A female patient with rupia, a skin condition, had been photographed at the Bristol Infirmary. To some workshop participants, the picture was preferable to that of William T., a West Riding Asylum patient whose severe case of psoriasis was captured in an intriguing picture of 1895, in which he appeared in front of a studio backdrop of a woodland scene. Whilst William looks directly into the camera as he stands completely nude, the female patient has had both her mid-section and head covered in an attempt at both anonymising her and preserving her modesty. Some participants praised this anonymising effort; others thought it further ‘pathologised’ the patient by transforming her into a much more recognisably ‘medical’ specimen. The background to each picture also proved an interesting talking point: while both images depicted skin conditions, the settings – the tiled bathroom and the woodland backdrop – significantly altered how they were read. Was the artistry of William’s portrait problematic in its ‘non-medical’ character, or was it an effective way of recording his condition?

William T., photographed at the West Riding Asylum in 1895. West Yorkshire Archive Service/Wakefield and the South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Trust.

Even before our discussions, though, I was being forced to think about the photographs in new ways. We’d sent the images we were using to be printed and laminated, and when we arrived in Huddersfield they were waiting for us in a brown envelope. Sorting through them, I quickly removed one of the images we had planned to talk about. The photograph of a woman’s severe bedsores – an all too common affliction for chronic and immobile asylum patients – was suddenly much more shocking when it was A4 and glossy. I was wary of confronting our participants with such a graphic image of open wounds, and put it to one side. This in itself raises further issues: I didn’t want to appoint myself as ‘gatekeeper’ of the images, but I was also aware that some people might find the image much more distressing than a photograph of a skin condition.

Some of our workshop pictures.

Throughout the day, several participants explicitly addressed the issue of ethics and how we use such photographs. For some who worked in medicine, maintaining patient anonymity and dignity was an ongoing issue that they could compare and contrast with the nineteenth-century context. For some participants, the re-working of genuine asylum photographs into dark, gothic illustrations was a positive way of generating discussion about the history of psychiatry; for others, it risked turning real patients into monstrous tropes representing the imagined horrors of the asylum. But for all of us, the photographs had been a productive and interesting way in to histories of the nineteenth-century asylum: more direct and more ‘human’ than a book. In looking at the image of William, we had glimpsed the medical work of the asylum but we had also glimpsed something of the real people at its heart. And it was for this reason that we were all agreed on the ethics of re-use when it came to medical photographs: the people in them gave the images a weight and resonance that called for responsibility and care in their use, whatever that may be. It’s that key point that I’m keeping in mind as I consider continuing to use these photographs – because, as we neared the end of the workshop, it struck me that a similar session could be equally as productive for some of my students at QMUL…

[…] The Historian: Workshop report: The uses of historical medical photography […]