“It’s a strange thing, magical, but ordinary. Everyone needs it, wants it, yet it is taken for granted. No one really understands it, yet we make rules, measurements and pronouncements as if we do.”

“It’s a strange thing, magical, but ordinary. Everyone needs it, wants it, yet it is taken for granted. No one really understands it, yet we make rules, measurements and pronouncements as if we do.”

No, this is not one of those riddles where the answer turns out to be an egg. It’s the opening of ‘The Night Husband’, one of the short stories in the volume, Spindles: Stories from the Science of Sleep, published by Comma Press in 2015. The protagonist suffers from a little-known sleep disorder called Paradoxical Insomnia. Unable to feel rested sleeping alone, the main purpose of her boyfriend, Alan, (with whom she has nothing in common) is to cure her sleep problems. With gentle irony, the author, Lisa Tuttle, captures not only the misery – the sheer desperation bordering on madness – that results when something as basic as sleep seems unattainable; but also the fractured nature of relationships in modern city life, which forms the context of the action.

Spindles is a collaboration between fourteen creative writers and eleven scientists. One of its editors is Professor Penelope Lewis, a neuroscientist working on the health benefits of Sleep Engineering. Sleep Engineering is the emerging science of how we can manipulate sleep to the greatest benefit to our health. An intriguing aspect of this is ‘Targeted Memory Replay’ – the use of smells and sounds to trigger memories during sleep. This has great implications for our mental and emotional health as it is believed to have the potential to benefit those suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. This is the topic of another of the short stories, ‘Left Eye’ by Adam Marek.

In bringing the work of contemporary scientists to a general audience the volume also draws attention to a fact that is important for our understanding of the past, namely that sleep changes over time. Our understanding of sleep changes as science advances new categories and explanations for sleep and its disorders. As Lewis points out in her introduction, the way we view sleep changes across time and culture, and so do the stories that we tell about it. In the genres of fairy tale and myth, sleep is mystical, preserving beauty, innocence and glory from the taint of the waking world – think of Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, or King Arthur. In the Spindles version, ‘My Soul to Keep’, by Martyn Bedford, Sleeping Beauty is a depressive teenager suffering from hypersomnia – another story of the relationship between sleep and disintegration in modern life. In Shakespeare’s plays sleep provides a window onto the guilty souls of Lady Macbeth and Richard III. In ‘A Sleeping Serial Killer’ and the Afterword, M. J. Hyland and Isabel Hutchison explore the evidence on whether bad dreams really reveal our darkest impulses, or serve some other function.

It is not just at the level of theory, however, that sleep has changed over time. Social and environmental shifts have fundamentally altered how people experience sleep. In the 1990s Thomas Wehr conducted experiments on sleep and artificial lighting that suggested that in an environment of purely natural light-dark cycles people experience bi-phasic sleep – that is, sleep is broken into two phases with a period of one or two hours of wakefulness in the middle of the night. Wehr discusses this in the Afterword to ‘In the Jungle, the Mighty Jungle’, which reimagines how prehistoric man may have experienced sleep.

Historical research into the changing nature and culture of sleep is at a relatively early stage. Some of it is mentioned as a background to the work that inspired Spindles. The ground-breaking work on evidence of bi-phasic sleep in the early modern period was done by Roger Ekirch in the last decade. His article ‘Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles’, American Historical Review (Apr, 2001) and subsequent monograph At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (W. W. Norton, 2005) uncovered numerous references to ‘first’ and ‘second’ sleep in pre-industrial Europe. Sasha Handley’s research into sleeping environments and routines in the long eighteenth century resulted in Sleep in Early Modern England (Yale University Press, 2016). William MacLehose is currently researching sleep in medieval science and medicine, and my own work at Queen Mary seeks to develop our understanding of the place of sleep disorders in magic and medicine in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

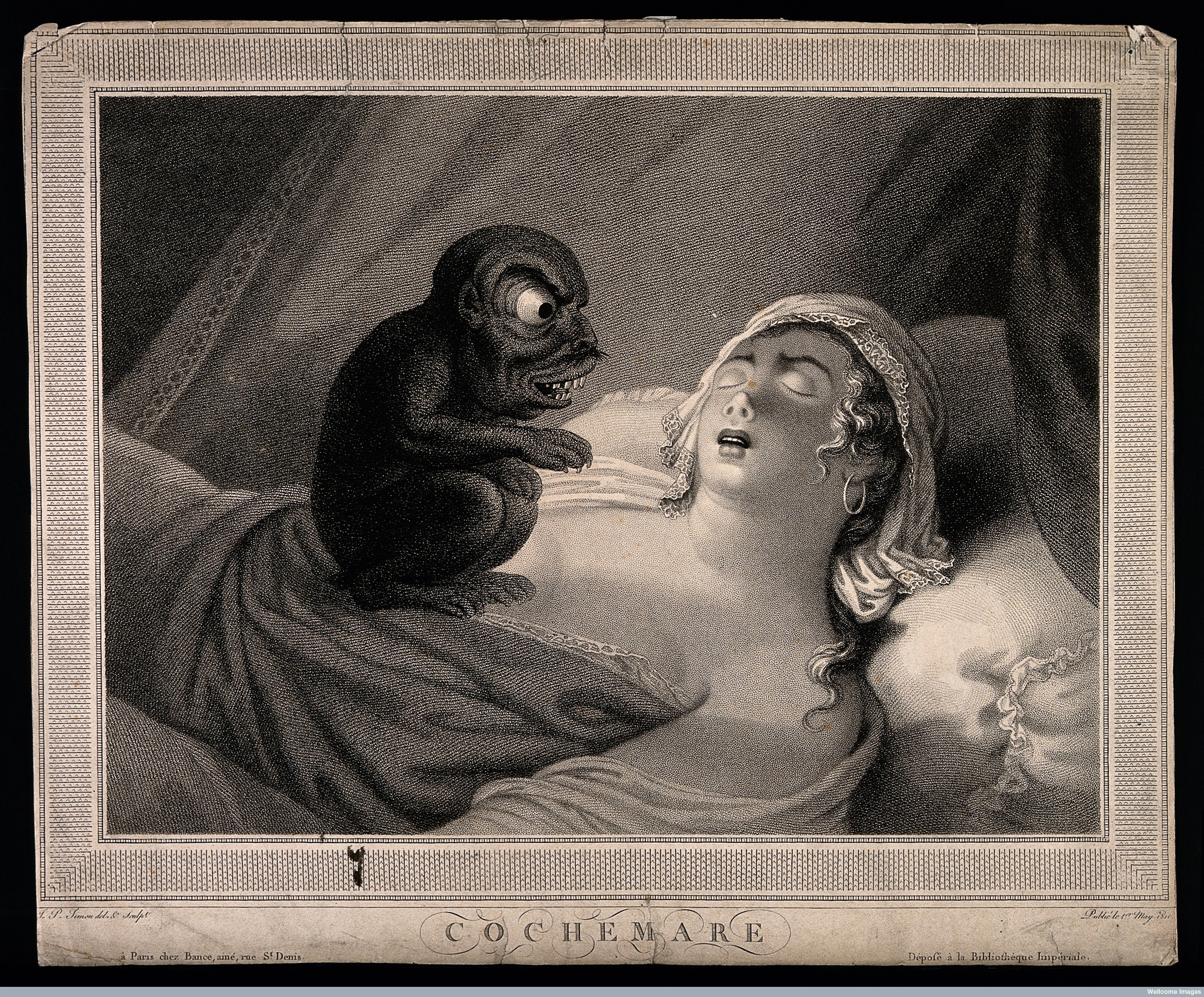

Historical research into the changing nature and culture of sleep is at a relatively early stage. Some of it is mentioned as a background to the work that inspired Spindles. The ground-breaking work on evidence of bi-phasic sleep in the early modern period was done by Roger Ekirch in the last decade. His article ‘Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles’, American Historical Review (Apr, 2001) and subsequent monograph At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (W. W. Norton, 2005) uncovered numerous references to ‘first’ and ‘second’ sleep in pre-industrial Europe. Sasha Handley’s research into sleeping environments and routines in the long eighteenth century resulted in Sleep in Early Modern England (Yale University Press, 2016). William MacLehose is currently researching sleep in medieval science and medicine, and my own work at Queen Mary seeks to develop our understanding of the place of sleep disorders in magic and medicine in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Arts Council of England, Spindles is an indication of the current recognition amongst funding bodies that sleep is an important area of research for our society to invest in and for the general public to engage with. In coming years we will be seeing further publications, in history and other fields, that will develop our understanding of this ‘magical, but ordinary’ phenomenon that is a part of all our lives.