Tudor Portrait Miniatures at the Fitzwilliam Museum

Portrait miniatures of the Tudor and Stuart periods continue to delight audiences close to half a millennium after their creation. Considered a particularly English art form brought to perfection by Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547–1619) and Isaac Oliver (c. 1565 – 1617), surviving examples now constitute tantalisingly intimate and brilliantly colourful glimpses of royals, courtiers and wealthy citizens of their age. Portrait miniatures lent themselves to being vehicles for personal and secret mottos and symbolic tropes. The use of clever allusion and hidden meaning was highly prized in Elizabethan culture and still fascinates us today in the writings of such period authors as Spenser, Shakespeare and Johnson.

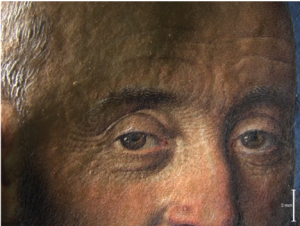

By their very nature, portrait miniatures would have been exclusive, portable and private objects, typically set in delicately carved and turned wooden or ivory boxes, but many would have been hidden centrepieces within precious metal lockets studded with gemstones and enamel motifs. Hilliard, in his unfinished treatise on the ‘Arte of Limning’ describes how ‘limning work’, i.e. miniature painting, “…is to be viewed of necessity in hand near onto the eye.”[1]

Miniatures in considerable numbers survive to this day, and the works of the two biggest names on the scene were recently the focus of a major exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery entitled Elizabethan Treasures: miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver. The show was state of the art and well visited. But the curious visitor still faced great challenges: the light-sensitive exhibits were all displayed in dimly lit cases, set back from the viewer behind thick, protective glazing. Magnifying glazes were made available to help overcome these necessary barriers, but the experience was far from the intention expressed by Hilliard.

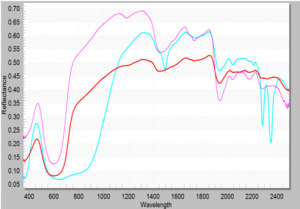

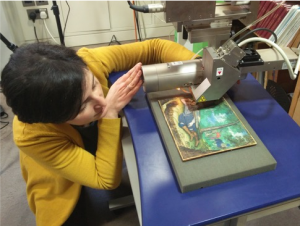

In the conservation lab of museums however, miniatures can be explored down to the individual pigment particle by specially trained conservators and heritage scientists. Non-invasive technical imaging and analysis can reveal secrets about the miniatures’ make-up and later changes that have otherwise gone unnoticed. At the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, an innovative research project focusing on the oeuvre of Isaac Oliver, Secrets of a Silent miniaturist, has been ongoing since 2016. The project aims to collect comprehensive datasets from a representative group of miniatures associated with Oliver, who, unlike his teacher Hilliard, left no written statements about his life and art, and therefore remains an elusive artistic figure, despite his great artistic talent.

The analytical protocol employed within the research project builds on the more limited methodology for technical miniatures research established in the 1980s, expanding the investigative means to match those employed on illuminated manuscripts today. Illuminations, on a material level, are directly comparable with miniatures.

The main aim of the project is to make the collected data available to a wide audience through an online resource. Whether scholarly or public, the resource would allow its users to explore and compare the miniatures in minute detail to an unprecedented degree through the technical images and analytical data. This could serve the purposes of attributional discussions amongst art historians, address the curiosity of school children learning about the famous sitters, inspire artists interested in historic materials and methods of depiction, and many more applications besides.

[1] Thornton, R.K.R. & Cain, T.G.S. (eds), A Treatise Concerning the Arte of Limning by Nicholas Hilliard, Carcanet New Press, 1981, p.87.